Media coverage of Africa is failing in the West. The news industry has been hit hard with the advent of the Internet, causing budget decreases and, in turn, less international coverage. Only a few western news bureaus remain stationed in Africa, which is the second largest continent in terms of both land mass and population. In Canada, a country with some of the most culturally diverse cities in the world, the Globe and Mail is the only major news organization with a bureau established in Africa. This has created a heavy reliance on wire stories, which often lack the depth and detail that good journalism deserves.

There is a tree in Somalia that, after it blooms, shrinks back into the ground before reappearing somewhere else. Maryan Issa calls it the travelling tree. Issa moved from Canada to Bacadweyn, a small village in the Puntland region of Somalia, when she was nine years old. She lived with her family on a plot of land with a well and no electricity. She would wake up to the caller’s prayer, go to her classes, and spend her afternoons exploring the wonders of the countryside with her father. “It was such a carefree life to live,” she says. “I lived there for two years and I didn’t hear one gunshot.”

Issa, now 21 years old, is a nursing student at Ryerson University. She describes her time living in Somalia as the best years of her life. The Somalia she knows to exist, however, is not the Somalia she reads about in her Twitter feed.

Media coverage of Africa is failing in the West. The news industry has been hit hard with the advent of the Internet, causing budget decreases and, in turn, less international coverage. Only a few western news bureaus remain stationed in Africa, which is the second largest continent in terms of both land mass and population. In Canada, a country with some of the most culturally diverse cities in the world, the Globe and Mail is the only major news organization with a bureau established in Africa. This has created a heavy reliance on wire stories, which often lack the depth and detail that good journalism deserves. What the west consumes has a firm footing, not in context, but in the historical narratives that have shaped the western conscience. “Africa to (Western media) is still about the four horsemen—Conquest, War, Famine, and Death. With a healthy leavening of corruption and bouncing bare breasts thrown in to make life more interesting,” says Tim Knight, a veteran international reporter from South Africa.

The first time I ever spoke to Knight, he was sitting at a patio table on the roof of a Toronto pub. He explained, in thrilling detail, his experience covering the Congolese conflicts in the 1960s for United Press International. “Trust me,” he said from under the wide brim of a leather hat, “You want to be out in the field with all of the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.”

A lack of such out-in-the-field reporting has left a void in international journalism. Very few western journalists have a home base in the continent, meaning much of the responsibility to report about Africa’s 54 countries is left for parachute journalists or freelancers. Pius Adesanmi, an African studies professor at Carleton University and the author of You Are Not a Country, Africa!, says Africa’s coverage is currently stricken by two extremes: biased and inaccurate coverage, or no coverage at all. Biased and inaccurate coverage usually results from the in-and-out tactic of parachute journalists, or, as Adesanmi likes to call them, Hilton hotel journalists. “They are lodged here in their Hilton hotels in capital cities, and they sip their orange juice in the morning, and they look out of their windows. And the Africa they see from their Hilton hotel window is what they report back to the west.” The continent is represented as a country and the humans are represented as numbers.

In March, scholars from around the world joined to address this issue of misrepresentation from the American channel, CBS. An open letter to the executive producer of CBS’s 60 Minutes reads, “Africa only warrants the public’s attention when there is disaster or human tragedy on an immense scale, when Westerners can be elevated to the role of central characters, or when it is a matter of that perennial favorite, wildlife…it badly disserves the news viewing and news reading public.”

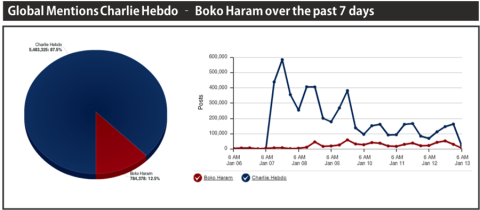

When African news is not being portrayed to the public through a skewed lens, it’s often not being portrayed at all. On January 3, for example, the Islamist terrorist group, Boko Haram, began a massacre of approximately 2,000 people in northern Nigeria. It took two weeks for the story to gain mention on a front page.

In a field that’s dominated by timeliness, it’s odd that western media didn’t pounce on the story sooner. But how could they? They had a duty to follow the 3.7 million people who were marching through Paris to commemorate 17 victims of terrorist attacks in France. “Je Suis Charlie” reached headlines around the world in honour of the 12 Charlie Hebdo journalists who were killed. Social media blew up, world leaders banded together in solidarity, and for a moment, it seemed as though the rest of the world had stopped.

The media’s agenda remained unchanged until people around the world started sharing the Boko Haram story on their online feeds. “I am Charlie” became, “I am Charlie—Let’s not forget about the victims of Boko Haram.” A slight nod of acknowledgment echoed throughout the western world, but it was clear, as General James “Spider” Marks told the CNN, that “black West Africa” just wasn’t a priority. “I don’t think (the media) has come to an assessment of just how geopolitically important the continent has become. It’s the youngest in matters of innovation and in matters of market,” Adesanmi, a native Nigerian, says. “Politically and economically, I think the west has caught on…but the media is actually behind all the factors of Western society in terms of appreciating what’s going on in Africa at the moment.”

Social media users also attracted global concern over a Boko Haram attack that occurred just nine months prior. The terrorist group kidnapped 276 girls from a northeastern village in Nigeria. Ibrahim Abdullahi, a Nigerian lawyer, voiced his concerns on social media and, with a few clicks on his keyboard, triggered the #BringBackOurGirls hashtag. The hashtag was used across the world, and eventually gained the attention of western public figures like Michelle Obama. Issa says that despite bringing attention to the event, however, the hashtag simplified a very complex issue. What it did do was start a conversation that everyone—including citizens of Nigeria—could participate in.

A rise of citizen journalism is inevitable with the freedoms of the Internet. However, the problem with citizen journalism is just that—freedom. Unlike traditional media, it’s a practice that’s tied to personal ethics as opposed to professional guidelines. There are no guarantees of accuracy or objectivity, which gives content a “consume at your own risk” staple. Many journalists and organizations remain wary of this rapidly emerging method for sharing news, mainly for the reason that it depletes the trustworthiness of journalism. “I’m not very sympathetic to those kinds of complaints—they come from people who are losing sales,” Adesanmi says. “Yeah, it’s got a downside, but look at the kind of voice it’s given to millions, who otherwise have no voice whatsoever.”

Of course, citizen journalism is not the be-all and end-all to poor coverage of African news. Poor coverage is the result of hundreds of years that are packed tight with colonialist ideals and stereotypes and is not something that can be fixed overnight. However, the void that the Internet once created in international reporting is now being filled with its very own users. This is crushing the notion that Africa needs to be spoken for by the West, and pushing recognition beyond the “four horsemen” narrative. The Internet is the seed, if you will, for the travelling tree of journalism, holding the millions of voices that allow western coverage to dig its roots into the realities of Africa. “A good story is a good story, no matter where it appears,” Knight says.

Courtney Miceli

Freelance Journalist

www.twitter.com/courtneymiceli