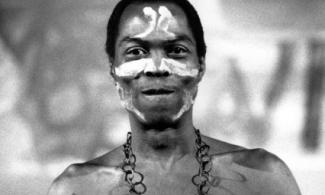

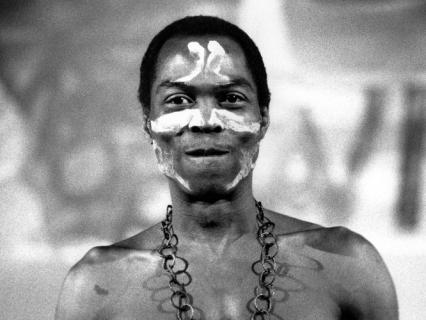

The first time I watched Fela perform was in the mid-1970s at the Enugu Campus of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Then, he was lusty and nimble. He sprang across the stage, as he danced, sang and played both the piano and tenor saxophone. Every move he made was mirrored in the sound of the music, as the drummer and the other percussionists followed his every move with their beat. His band members were decked out in pink “Crepelin” outfits.

The first time I watched Fela perform was in the mid-1970s at the Enugu Campus of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Then, he was lusty and nimble. He sprang across the stage, as he danced, sang and played both the piano and tenor saxophone.

Every move he made was mirrored in the sound of the music, as the drummer and the other percussionists followed his every move with their beat. His band members were decked out in pink “Crepelin” outfits. His dancers were scantily clad, and they seductively swirled and swayed their hips to the rhythmical throbbing of the Africa 70 (the name of Fela’s band in the 1970s). Over all, his music was of unequalled excellence and his stage work, extraordinary. It was obvious that this maestro had taken music and entertainment in Nigeria to new heights.

The last time I watched him was in the early-1990s in Washington, DC, at the Kilimanjaro Night Club. By then, his years of struggle against the evil oligarchy that ran Nigeria had taken a toll on him. As such, he was not as gorgeously attired and his band was not as splendidly arrayed. But he remained his defiant and indefatigable self, his band, unflappably first-rate, his dancers, vivacious and matchless, and his music, exquisite. In his Yabis (verbal interlude), he spoke about issues ranging current affairs to international economics, and African history. A man, obviously impressed, like everyone else in the audience, by his extensive knowledge and incisive mind shouted, “Fela vacancy dey for Howard O. Make you go dey teach for Howard University O.”

It was these qualities made evident on these two occasions that distinguished the phenomenon of Fela Anikulapo Kuti as a trailblazing musician and entertainer with the learning and versatility of a teacher, oratorical flourishes of a preacher, and the deep insight of a philosopher. He was a nonconformist; everything about him deviated from standards of orthodoxy. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Nigerian popular music was under the powerful influence of Western, especially American, music. Nigerian musicians desperately needed to sound like James Brown, Otis Redding, the Rolling Stones, etc. Fela came up with something distinctly new: it had the pronounced base-line of Rhythm and Blues, heavy percussions of traditional African music and well-defined lead guitar as in Highlife music – all - laced with elaborate and dainty horns (trumpet, trombone and saxophone) and intricate piano of Afro-American Jazz. It was a unique musical genre. He called it Afro Beat.

The vocalism of Afro Beat also defied convention. Unlike the soft and velvety singing of Highlife, and similar styled singing, or the embellished feigned American accents of Nigerian Pop musicians, the vocals for Afro Beat was loud and coarse. It reflected the vibrancy and upbeat of Nigerian, especially Lagosian, life. Its lyrics, for the most part, were in the Nigerian mass language, Pidgin English, because they bore messages for all and sundry in Nigeria and beyond. Unlike the usual romantic platitudes and praises for the wealthy and powerful of Nigerian music, the lyrics of Afro Beat were the words of a social crusader.

The arrogance, greed and the insensitivity of the Nigerian power elite, and their roughshod over the passive and timid Nigerian masses offended Fela’s natural sense of justice. So, like John Brown who, driven by his moral revulsion for racial injustice, set out, on his own, to overthrow the institution of slavery in the American South, Fela was on a one-man mission to cure Nigeria of social injustice. This mission found expression in his music. With his poignant and defiant lyrics, he brayed against official corruption, mass poverty, police and military brutality, gutlessness of the Nigerian populace, etc. His music resonated among Nigerians because it encapsulated their moods and sentiments: hopes, frustrations, hunger for a good life and longing for social justice.

And like John Brown, Fela paid a heavy price for his crusading passion. The persecution of Fela by different Nigerian governments culminated in the burning of his house by soldiers in 1977. As the soldiers rampaged through his house, before setting it ablaze, they assaulted his guests, beat up his band members, raped some of his dancers and threw his 78 year old mother out of a 2nd floor window. She later died from the wounds she sustained from the fall. His mother, Fumilayo Ramsome-Kuti, was a foremost nationalist and politician, a leading figure in the Nigerian struggle for independence. In the mournful song, “Unknown Soldier”, Fela described the burning of his house and the killing of his mother, Fela eulogized her as, “Political Mama, Influential Mama, Ideological Mama, and the only Mother of this Country”.

John Brown failed to overthrow slavery in American. He was captured and executed by the government. John Brown’s assault on slavery may have seemed foolhardy, ineffective and meaningless. However, it is from such “numberless diverse acts of courage and belief that human history is shaped”. The seed Brown sowed with that selfless stand for an ideal germinated, and years later, bloomed, and through its many branches, generated forces that broke down racial barriers and oppression in America. Similarly, Fela, failed to change the Nigerian society. But then, he left his indelible marks on it. Apart from his indigenization (of rhythm and vocalism) of popular music in Nigerian, he charted a totally new course for Nigerian music. It became a possible tool for social crusade, mass mobilization, and awakening the aspirations and consciousness of the masses. His music continues to reverberate. It continues to strike a deep chord in Nigerian minds because of its amazing splendor and the incontrovertible pertinence of its message.

Upon his death, Lagos, the bustling, boisterous commercial capital of Africa, came to a somber standstill. Gathered to pay their last respect was a throng – unparalleled in its size and incongruous in its composition. The incomparably large crowd, made up of the rich and poor, learned and ignorant, bumpkins and sophisticates, Nigerians and foreigners, etc, gathered in solemn veneration for one of the leaders of our time. Leaders are not just those that occupy positions of political power and influence. Actually, real leaders do not have to occupy exalted positions in government to lead. A leader has a following because he possesses that indescribable, indefinable magnetism that powerfully and irresistibly draws people to him. People also follow a leader because leadership represents a current in history. And a current, naturally and effortlessly, moves and carries people along.

Undoubtedly, Fela left a footprint in the sand of time, he made history. The father of modern Zionism, Theodore Herzl, once wrote that, “history is nothing but noise, noise of arms and noise of advancing ideas”. Fela’s noise was the noise of advancing ideas. He advanced the ideals of freedom and social justice with the power of music.

Tochukwu Ezukanma writes from Lagos, Nigeria