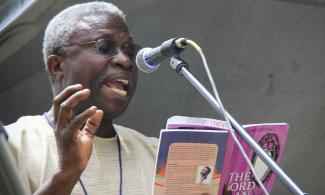

Professor Niyi Osundare, poet and teacher clocks 70 today. In this online interview with ANOTE AJELUOROU from his base in the University of New Orleans, U.S., Osundare reflects on life at 70, with commentary on the Nigerian situation

How significant is today to you?

Yes, the Biblical three score and ten: a milestone indeed and in truth! It is by no means a mean achievement in a country, where the male life expectancy is something between a dreadful 45 and 50 years. I have been exceedingly lucky, with regards to the kind of good health I have had, and the fact that I survived two traumatic events: the attack by the yet unknown, yet un-apprehended hoodlums, who axed my head in January 1987 and very narrowly missed my brain. Then there was Hurricane Katrina in August 2005, which came so close to sweeping away my wife and I in New Orleans. But I also know that this ‘luck’ is both a gift and a challenge: a profound reason to rededicate my life to the struggle for a just and humane world.

How fulfilled are you as a writer and teacher?

Fulfilment? Ah, that luxury is for the smug and complacent. I am humbled by what this farmer’s son from Ikere Ekiti has been able to achieve, and grateful to those who have helped me along the way, especially my parents, my own family, my teachers (yes, my teachers!), my colleagues, my publishers, my students, and many other benefactors in the different parts of the world my professional career has taken me to. To be soberly frank, life hasn’t been a bed of roses, but neither has it been a Golgotha of thorns.

Could you give a little background to your journey so far, starting from your beloved Ikere-Ekiti and how it shaped and sharpened your creative consciousness?

Well, I think most of my response to this question is now in the public domain – in a manner of speaking – from virtually all my previous interviews. In a nutshell, let me say again, that the kind of parents I was lucky to have; the kind of Ikere-Ekiti, and the kind of Nigeria I grew up in shaped the course of my life. A tirelessly hardworking father, a farmer who also had some time for songs and the drum, and rippling humour and repartee; a pensive, morally tenacious mother, both of whom told me there was no honest alternative to hard work; the pioneers of Western education in our extended family, my egbon Tayo Ayodele, Pius Olowoyo, Layo Idowu, Oluremi Jegede, Peter Ayodele and Sanya Toso Gbangba, who made education and enlightenment so attractive, so achievable.

Tayo Ayodele was particularly influential as egbon, leader, teacher, brother, and mentor, all rolled into one. As I said in my first Selected Poems, which I dedicated to him, through his acts of leadership and vision, Oga Tayo taught me “abiding lessons in love and generosity.” He introduced my colleagues and I to formal stage drama and theater in our annual Ule Asa end-of-year “entertainment.” I was a very inquisitive, intellectually relentless child. Oga Tayo nurtured that trait and saw in my future what many others did not see. What others misconstrued as behavioral and mental frivolity, he saw as flair and promise; what they thought was a too-know habit, he discerned as intellectual adventurousness. Hardly a day passes without my remembering Oga Motayo.

And, of course, Ikere-Ekiti was vibrant with its various festivals – Egigun, Oliki, Ogun Oye, Oloba, and of course, Osun, the one that was right in the centre of Ule Asa temple of belief. Olosunta is the commander of all festivals, a prodigiously creative, painstakingly orchestrated drama of worship and wonder. The heavy sound of Agba, the man-size drum of this deity, resonates in many of my lines… Ikere in those days was joyously multi-ethnic: Hausa-Fulani, Igbo, Urhobo, Agatu, Ebira, Idoma, etc. were all around, exchanging languages, song, cuisine and dance styles with Ikere natives. That was it before the politicians fouled up the country, provoked a devastating civil war, and scattered the Ikere ideal.

And, oh yes, Ekiti in my youth were a people noted – and respected – for their hard work, integrity, tenacity and frugality – people who put the human being over and above material possessions. It was an Ekiti revered for sterling brainpower, not ridiculed on account of stomach infrastructure.

Your poetry reflects the marketplace parlance, of accessibility, commonality, and communality. At what point did these poetic aesthetics dawn on you and how did you hone it to such perfection as it is today?

Very early in my academic and writerly career, like Pablo Neruda, the immortal poet of Chile of the world, I made an abiding pledge that the people would find their voices in my songs. Accessibility, the urge to communicate, the spirit of sharing, the concert (or conflict) of minds… these are essential ingredients of art. As I said in one of my monographs on literary communication, art thrives in the process of the private agitation made public; what the artist has, s/he seeks to share. The festivals songs, the proverbs, wisecracks, folktales, etc. that I heard and loved in my childhood days opened my eyes, ears, and mind to the importance – and imperative – of communication in art. Simplicity, not banality, suppleness not grossness, people-orientedness not privatist musing, a touch of obscurity, but surely not obscurantism.

Of the African poets, we read in secondary school, only JP Clark and Okara proved relatively accessible. We admired Soyinka and Okigbo and wrestled heroically with their poetry, but little came from our effort. Somehow, I began to feel that there must be other ways of writing poetry that would not build a wall between the poet and the reading/listening public. A song, sweet but strong… This was very much in my mind, when I was working on Songs of the Marketplace, my first book of poems. That very title was the invention of Professor Abiola Irele, whose New Horn Press published the book. It’s not by accident that the opening poem in the book is “Poetry Is,” a title many readers have come to see as my poetic manifesto. My belief is that an artist who wants his work to be relevant to society; an artist, whose dream is the achievement of a more just, more humane society, cannot afford to put a wall of obscurity between himself and the society he wants to change. So, delicate simplicity and accessibility should be part of the aesthetics of literary engagement. In practical terms, if you want the people to respond to your song, you must raise a song that they understand.

This urge to touch and change, this dream for a better world has been close to the core of my literary and social ideology all these years. It was what led me to run a poetry column, Songs of the Season, later Lifelines in the Sunday Tribune for over 30 years, before finding a new home for it in Sunday Nation in February this year. My experience as the ‘Bard of the Tabloid Platform’ has shown me the enormous impact of poetry when composed in the right language, disseminated in the right context, and aimed at the right audience. Those still in doubt should consider the massive popularity and impact of ewi performers in Yorubaland.

You have won accolades in your academic career. Which do you consider most significant?

All of them. And I thank the givers for considering me a worthy recipient.

After the Katrina poems and collection, what next might your readers expect from you? Did the poems help your healing from that traumatic experience?

Absolutely. Composing and publishing City without People: The Katrina Poems contributed in no small measure to my recovery from the hurricane’s indescribable trauma, in ensuring that Katrina never had the last word. Since the outing of that book, there has been no silence in the house of songs. Lifelines stir the tabloid pages every Sunday, and I thank my audience for letting me know they are there. A new book of poems is in the press and almost out, and The Eye of the Earth may get a younger brother/sister by my next birthday. Poetry grips me like a delectable obsession: I cannot think of any day without reading, talking, or writing a poem.

You are far away, yet so here at home. Will you be teaching in a Nigerian university after retirement?

Yes, the prodigal’s feet are itching for the way back home. Every grey hair on my head longs for the glistening touch of the Nigerian sun… You’re right: these many years have been a case of away-without-being-away; for this troublesome country called Nigeria is absolutely impossible to forget, to abandon. What with its histrionic insanities, its sweet bitterness, its tall palm trees and lilting rivers, its seductive mountains, its tuwo, akpu, iyan and amala, its drum and dance, its songs of eternal enchantment, the rhapsodic hips of its dancing angels…

My responsibilities and commitments on both sides of the Atlantic are many and varied. But I surely intend to spend more time in Nigeria and further strengthen my bonds with our educational institutions. My colleagues in the Department of English, University of Ibadan, have cleared my path to this new designation by recently facilitating my appointment as Visiting Professor during the summer break. I am told what is required are my mentoring and presence. I thank them and the university authorities for this wonderful initiative. Nothing excites me more wondrously than being in a university environment. That has been my root and roost for the past four decades. I look forward to sharing the little I have and tapping from the wells of my younger colleagues and our students. As always, it’s a mutually beneficial initiative. If this project runs well, I may end up looking like half of my 70 years!

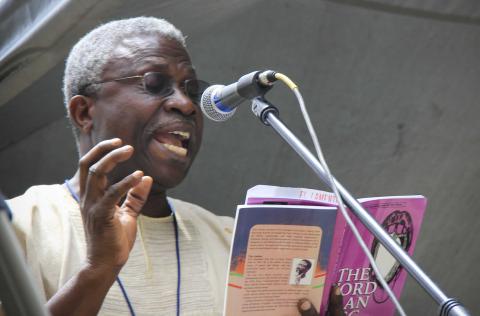

No doubt, your marketplace poetic sensibility gave birth to your recent poem, ‘My Lord, Tell me where to Keep your Bribe,’ an apt poem that captures the mess in Nigeria’s legal/judiciary, and by extension, all sectors of Nigerian life. Just how much of such poetry does the society need, especially among a people that read far less than is required?

The poem you mentioned demonstrated the enormous power of poetry, especially in this era of the social media. It went ‘viral’- to borrow the popular lingo of the cyber industry. I was surprised and delighted, then overawed by the sheer reach and resonance of the poem… Yes, the ‘marketplace sensibility’ – to borrow your fascinating phrase, makes it relevant, makes it urgent, makes it true, and makes it accessible and the poem will find the eyes and ears of the people. The enormity of venality uncovered in Nigeria’s Judiciary alarmed the decent world. The Judiciary, with its awesome life-and-death power, with that level of corruption? Those sworn to keeping the country free of criminality are themselves such agents and vectors of the grossest type of criminality?

How can a country survive, whose judicial system is so perverted?

Nigerians have seen the Law stood on its head in all kinds of ways; we have seen Justice miscarried, aborted, or misbegotten. We have seen all manner of ‘interlocutory and perpetual injunctions’ put Justice on hold. We have seen politicians, who lose elections rush to the courts to buy the victory they couldn’t secure at the polls. We have seen criminally rich politicians shop for compliant judges to sit over their cases. The wealth of many of our Lords is too gross, too conspicuous to have been honestly earned. But honestly, I never knew the rot was so abysmal. The Judiciary is the heartbeat of a nation, its legal and moral compass. What happens to a country with a terrible cancer in this vital organ?

Of course, it must be admitted that both the Bar and the Bench of the Nigerian Judicial system have many men and women of impeccable integrity. But let them see it as their duty to call out and expose the rotten eggs in their ranks. Otherwise, the pervasive stench will not spare their own robes.

You gave a lecture about corruption being the grand commander of the Federal Republic of Nigeria in 2012. Looking back then and now, what has changed, and what is likely changing?

Very little has changed, but in our critical circumstances, that little totals to much. We may say that four years ago, when I delivered that lecture, corruption walked the streets like a giant, bold, hailed, lionized, and feted at every turn. But today, that giant has shrunk a little bit, and when it walks the streets, it casts furtive looks across both shoulders like ole inu ireke (poacher on a sugarcane plantation). The EFCC seems to have leapt out of its stupor. Its arrests have been criticized as selective, but they have opened up strongholds loaded with millions of raw American dollars and given the nation a lesson in what Tatalo Alamu, The Nation’s relentless wordsmith, has called “the political economy of kleptocracy.”

Today, if you are a corrupt official being chased around the streets of Abuja for taking part in looting the national treasury, you are not likely to have the gates of Aso Rock thrown wide open for you by a sleaze-compliant boss. Corruption fights back. Yes, it does. And it has tons and tons of stolen money for its foul campaign. In the last analysis, corruption is too virulent a plague to be left to politicians and political jobbers to fight and vanquish. That virus has invaded every fabric of the Nigerian being. It is our civic duty to get it dislodged and exterminated.

A section of Nigerians have always cried out for the restructuring of the country for its true nationhood to emerge. After almost two years of Buhari’s ‘change’ government, does that call still seem legitimate?

‘Restructure.’ Oh, that word again! I think I have addressed this issue in my previous interventions, most recently in my Adekunle Fajuyi Lecture of July 29 2016. The political restructuring that would allay the fear of ethnic minorities?

Yes, I am all for that. ‘Fiscal federalism,’ that one also sounds good, politically correct. But I am for other kinds of restructuring. The restructuring of the present criminally iniquitous system that concentrates so much of our national wealth and power in the hands of a greedy and heartless few. The restructuring of a national value system, which places cash over character, power over propriety. The restructuring of a political arrangement in which ‘elected’ officials loot the national treasury through undeclared emoluments and countless constituency allowances…We must stretch the word ‘restructure’ beyond the pranks of political hawks intent on carving out juicier political fiefdoms for themselves. We must restructure the political semantics of the word ‘restructure’ itself.