If I ever had any illusion about the imminence of his demise, it vanished one Tuesday, mid-March, last year. At about 2.a.m. that starless night in Accra, I got a frantic call from my mother in Ilesha, my hometown, tearfully telling me that my father, and her husband of a little over 60 years had suddenly stopped breathing. The sad news threw me into a sudden turbulence. In my confusion, and with tears rolling rapidly down my face, I called my uncle in Ilesha. We fondly call him Broda Bode. I relayed the sad news to him and begged him to go to my father’s residence to verify what had happened and help sort out things.

Broda Bode responded with the speed of light. As he would later tell me, he rode his motorcycle to the place, without any headlight, and swept through the dark six-kilometre route like a hurricane. “Baba mi has truly stopped breathing o,” he told me, about one hour later, amid wailings in the background. “But I don’t believe he is gone,” Broda Bode hurriedly noted. “His body is still warm. In fact, he is on my lap as I speak.” That offered no comfort. I sank deeper in my confusion. With my father knocking hard at 100, I knew this day would certainly come. But strangely, I always thought he would, and should, be there for us for another 10 years.

That was my idea. And the idea had swirled round and round in my mind before this absolutely dark night. But with this scenario unfurling before me, I suddenly realised that no matter how potent an idea can be, reality is its master. ‘Perhaps, this is my night of reality, a night I should stop behaving like the wind and draw a line between conception and creation, between emotion and rational response. After all, when life ends, as it must, it often doesn’t do so with a bang but a whimper.

‘Ko si awaye ma lo’ I told myself in a melancholic soliloquy. (Transliterated, that Yoruba saying simply means: there is no one that has ever trodden this plane of existence without exiting.) ‘My father has passed,’ I struggled to cage my emotion as I began to call my siblings, one after the other.

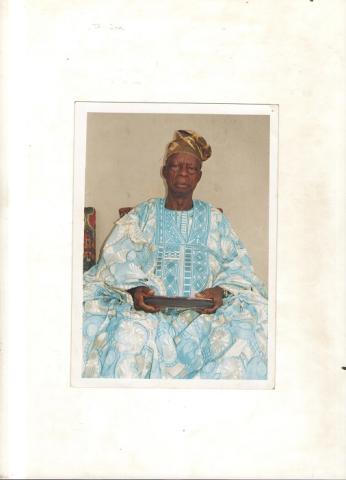

But exactly two hours after he was pronounced ‘dead’, my father, Elder Paul Ayodele Joshua Oshunkeye, the Baba Ijo of the Christ Apostolic Church, Igbaye, Ilesha, Osun State of Nigeria, ‘resurrected’. Broda Bode called me to say that he had begun to breathe again. Boy, did I go mad with joy!

As Dr. Bamidele Ogunwale, our father’s GP and a geriatric expert, later educated us, our old man didn’t actually die in March. He only served notice of his imminent departure by relapsing into hypoglycaemic coma. Whatever that means…

By the time I arrived Ilesha four days later, a Saturday, my father was already back in his elements. He sang almost endlessly. He joked with everyone. Baba Wale and Son! He called out as he normally did anytime I visited, and slapped my hand in a warm handshake. He was in an expansive mood, totally oblivious of the pain tearing my heart apart. He told beautiful tales about where he went, and where he believed would be his final destination when his sojourn on earth shall end. He spoke of a beautiful, shining light that illuminated everywhere he went. He spoke of some 21 Bishops, clad in immaculate white robes, who administered Holy Communion to him and anointed him with oil. His face radiated joy and his mien weaved a banner of peace as he described where he had been as a place of grace and glory, wondering why the journey didn’t continue ad infinitum. And he was not hallucinating.

So, the journey continued. And Pa Oshunkeye continued to enjoy his pounded yam with efo riro, washing it down, sometimes, with fresh palm wine. However, I didn’t need any seer to tell me that the man I had known for almost 60 years as my father was signing off. I resolved to call him every day from that moment.

Sadly, ‘NEPA and network failure’, as we call it in this clime, conspired to block me from talking to my father before he slipped into an irreversible coma on Monday, October 12, 2015. Cable News Network, CNN, had invited me and 19 other past winners of its overall prize in the African Journalist of the Year Awards, to Nairobi, Kenya, where we were honoured at a gala. The landmark event marked the 20th anniversary of the prestigious awards. I left Accra in the night of October 6 for the milestone event, held between October 8 and 10, 2015, and I made sure I called my parents every night.

Sadly, my father’s phone went dead on the eve of my departure from Nairobi on October 11. By the time I called the line, the next day in Accra, I got a shocker. My mother told me that Papa had gone to bed the previous night and had neither woken up nor responded to any stimulus. As it was in the mid-March’s episode, my mother was inconsolable again. I called Dr. Ogunwale, he told me that there was little medical science could do to help Papa. “Just be praying for Papa,” he said sympathetically. “Just make him as comfortable as possible.”

I got the message, and quickly switched from asking God for healing for Elder Oshunkeye to: if it was time to go, God should make it easy for him. My siblings and I were united in that prayer. And at about 10 p.m. on Thursday, October 15, time froze finally and perpetually for my hero. The greatest dad God ever created went the way of all flesh. Elder Paul Ayodele Joshua Oshunkeye returned to His Maker. And heaven has been rejoicing at his home-coming because he returned like an all-conquering Army General. He came, he saw and he conquered.

As we return his mortal remains to mother earth this Saturday, February 6, 2016, I cannot but recall the giant footprints my hero left on the sands of time. My hero attended school for just one day after which his father withdrew him into his cocoa plantation where, in his judgment, he felt the young Ayodele would be more useful. So, every blessed day, the young Ayodele headed for the farm as early as 5a.m. while his peers prepared for school at daybreak. That trauma so haunted the young man that he swore that if he ever gets married and have children, he would give all of them the best education his money could provide. And my hero was true to this resolve.

Twice I was at the brink of not getting education, twice this man sacrificed all he had to return me to the path of ‘salvation from poverty,’ as he often said. For instance, after my primary education in 1968, he enrolled me as an apprentice draughtsman. I combined that with newspaper vendoring for two years. Later, he took a loan from a thrift collector and bought the entrance examination form for Ilesa Grammar School. Fortunately, I wrote the exam, passed and was admitted into the school in January 1970.

In 1973, my education almost stalled again after passing my promotion examination from Form 4 to Form 5. Reason? My parents couldn’t raise enough money to pay my fees. With help coming from nowhere, my hero encouraged me to collect my S. 75 Certificate and hunt for job as a Primary School Teacher. I saw my father weep for the first time in my life as he gave me that instruction. He would, however, reverse himself few weeks later when he sold part of the only possession he had, a plot of land, to an uncle so he could pay for my final year at Ilesha Grammar School. He made similar sacrifices for my seven siblings. He had eight of us-seven boys and a girl. To the glory of God, we all had good education and are doing well in our chosen careers.

My friends mocked me when they saw me weeping at the demise of my father. Indeed, I wept in gallons. My tears didn’t pour, they rained. I wept because here was a man who stood like Zuma Rock for his children where even some men of means had faltered and failed. He gave his life, as it were, to secure our tomorrow. Nothing was too much for him to give up in order to make us happy.

I grew up knowing my father as a gardener and a subsistent farmer. He went to the farm at the close of work each day. And he planted anything and everything, ranging from vegetables to yam to rice. My mother, too, sold anything from ogi (akamu) to pounded yam (iyan olobe). She also sold tinko and ponmo. Like father, mother did all these with us from Monday through Saturday, and some Sundays, too. To feed and meet our basic needs, we all worked our fingers to the bones.

Sadly, despite their hardworking nature, poverty remained our parents’ constant companion for a long time. Father was so poor he had only two pairs of khaki trousers and shirts. He wore one pair to work and farm from Monday to Saturday, and reserved one for church on Sunday. Mother was never able to socialise because she had no befitting cloth. They had very few friends because they were poor. But they were rich in their souls and spirits. They never coveted anything belonging to their privileged relatives or neighbours. In their lowly estate, they were happy and contented. And God rewarded them at the goodness of His time. For them, the comforting words of Galatians 6:9 (King James Version) were not only precious, they were like opium: And let us not be weary in well doing: for in due season we shall reap, if we faint not.

Apart from giving us life and education that his means could procure, our father grounded us in some life-nourishing principles. He taught us solid lessons in honesty, hard work and contentment. He constantly warned us to beware of covetousness because a man’s life does not consist in the abundance of things that he possesses. He taught us to love and worship God; believe in ourselves; and be confident in the power of God to meet all our needs according to His infinite riches in glory through Christ Jesus. He taught us lessons in persistence and perseverance. He taught us how to ride the storms of life with faith, how not to stoop to folly. He taught us how not to chase after the wind because there is time for everything under the sun.

In practical terms, Baba Mi, my hero, demonstrated how to be an extraordinary father, an outstanding husband, a teacher of an uncommon kind and a generous giver. Elder Paul Ayodele Joshua Oshunkeye was a rare breed of Homo sapiens who God sends to this world once in a century.

Baba Mi, my hero, this is why all of us, your children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren celebrate you today. And we shall continue to celebrate you till we meet again in the City of God, which streets are paved with diamond and gold, and where there is neither day nor night.

Adieu, my hero. O digba, Baba Mi.