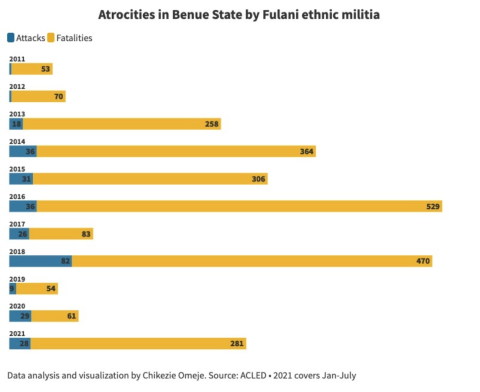

The Fulani militia has attacked the state at least 303 times since 2005, killing no fewer than 2539 people, nearly one-third of all the reported killings by the herdsmen in the country

Thirteen days to the election that brought in Muhammadu Buhari as president in 2015, Fulani ethnic militia killed about 90 persons in an overnight raid on Egba, a community in Otukpo, Benue State. Children, women, and men were murdered as the invaders burned down their houses.

Six years later, Otukpo has become a model for peace between the Fulani settlers and the indigenous Idoma while much of the state continues to burn in a lingering crisis over grazing rights.

The age-long conflict between farmers and Fulani herders in Nigeria has been most disastrous in Benue. The Fulani militia has attacked the state at least 303 times since 2005, killing no fewer than 2539 people, nearly one-third of all the reported killings by the herdsmen in the country, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).

Frequent clashes between farmers and pastoralists forced the state government to pass a law banning open grazing of cattle in late 2017. The Open Grazing Prohibition and Ranches Establishment Law requires livestock owners to buy land and establish ranches, prohibiting open movement of animals within the state. It spells out punishments, including five-year jail term or N1 million fine for anyone whose cattle graze outside a ranch.

But incessant attacks by the herdsmen have followed the anti-open grazing law. Fulani militia attacked the state 82 times in 2018, the highest of such violence in a single year. Hundreds of thousands of farmers have been displaced as a result and the state has faced its worst-ever humanitarian crisis since its creation in 1976.

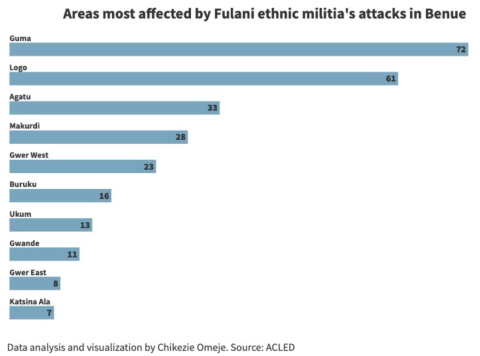

While other areas in Benue reel from the farmer-herder conflict, Otukpo has largely remained peaceful as only one attack and one death from the Fulani militia have been recorded since 2018. Some other places in the state have had more than 50 attacks each. Guma, for example, has been attacked by Fulani herdsmen for not less than 72 times and Logo has had 61 attacks.

What did Otukpo do differently?

Last month, at the Fulani settlement in Olena, a community in Otukpo, Fulani women busied themselves with chores around their huts. Their men had gone out to graze their cattle in designated areas.

It was early afternoon. Some of their male children were herding a flock of sheep within their habitation. others were playing around, some without clothes. Nearby, a group of farmers were returning home after the day’s work. They passed the Fulani’s abode and waved at the women who responded to the friendly gesture.

“That is how we have been living here over the years,” said a Fulani woman who was shy to speak to the journalists, refusing to say her name because her spouse forbade her from interacting with strangers. “We have not had any problems with the people. Everyone here is happy,” she added.

Despite the 2015 mass killing by the Fulani militia in Egba and the persistent wanton destruction in the state by the militia, Fulani settlers in Olena have found peace among the Idoma.

After the anti-0pen grazing law was passed, chairman of Otukpo Local Government Area, George Alli organized a stakeholders meeting, comprising all the district heads. At the meeting, Alli instructed the local leaders to get the data – names, population, and settlements of all the Fulani herders in their various communities.

“We were living with most of them even before the law came,” John Eimonye, district head of Otukpo said. “Some of them had spent 30 years and were integrated as part of us. We did not want to drive them in a hurry.”

In his district, Eimonye had conveyed a stakeholders’ meeting, this time, with clan heads who oversee the villages. Thereafter, they proceeded to the places inhabited by the Fulani to collect the data that would help him to know those who had been living in communities under his leadership.

Based on the instruction from Alli, Eimonye gave the herdsmen a six-month ultimatum to negotiate with landowners to allocate plots of land to graze their cattle. As the deadline passed, herdsmen who could not abide by the new arrangement were asked to leave Otukpo while those who obeyed stayed put.

“They had to decide how much they were going to pay to the owners of the land,” Eimonye said. “Once the ranches were established, the herdsmen knew there was a law to be obeyed and a new lifestyle.”

They agreed with the herders on a route they must follow whenever they are herding their cattle to the stream to avoid straying into farmlands and destroying crops which have been the root cause of the farmer-herder clashes across the country.

A committee which has the responsibility of assessing the level of destruction on farms by cattle was set up and farmers were asked to always report to the committee each time there was an infraction by the herders.

Farmers report to the community leader whenever the cows eat their crops. Then the leader would get in touch with the committee to assess the level of destruction. After the assessment, the community leader would invite the owners of the cattle to negotiate with the farmers on the appropriate compensation.

“The herdsmen do not hesitate to pay farm owners whenever their cattle destroy crops,” Eimonye said. “We have been able to manage the herdsmen in our midst because the chairman has kept us on our toes.”

Now Eimonye holds a meeting with the Fulani leaders on the 10th of every month where they discuss the challenges and solutions in their various communities.

Reciprocal security operation

In addition to setting up a committee that assesses the extent of damage on farms, there are livestock guards.

The guards who operate in all communities in Otukpo ensure that cows follow the route that had been agreed upon. Herders had agreed to always move along the power transmission lines since farmers rarely plant crops on that path.

“When we discovered that their cattle needed enough water, we decided to introduce the livestock guards who are like the police for livestock,” Igochie Ikwue, security adviser to the local government chairman said. “We had them stationed in various villages.”

The herdsmen had been given the schedule to herd their cattle to the stream and were required to always inform the guards whenever they moved. When it is time, the guards go with the herders to the stream and still accompany them to their homes.

Ikwue pointed out that the use of child herders is one of the reasons for frequent clashes because they tend to be careless with their cattle.

“When abandoned, the cattle enter into people’s farms,” he said. “They don’t know the difference between farmers' crops and grasses. It is the herder who is controlling them that knows when they are entering people’s farms and diverts them.”

Reason for the escalating crisis in some places, Ikwue noted, is that community leaders do not have control over their youth who often resort to violence when their crops are eaten up by cows.

“The Fulani man gets angry each time his wealth is tampered with and for them, the cow is their wealth. If you kill his cow, it does not go down well with him. Here in Otukpo, we warn our people not to ever tamper with their cattle,” Ikwue said.

The Fulani herders had also agreed to report identified Fulani herdsmen and to be held responsible for damage to farms if they failed to do so. The Nigerian government has often blamed Fulani herders who migrate from other countries in West Africa for the attacks on farmers.

“They know when they see strange cows,” said Udeh Adole, the clan head of Ai-Okopi. “Once when they discovered some strange faces who had run into Otukpo after rustling cattle in Kogi State, they informed us and quickly we mobilised our security men and chased them away.”

He said they would not have known if they were not informed by the settled herdsmen. Ai-Okopi is made up of two villages, Upu and Okpobeka. Here, herdsmen have been going about their normal grazing activities in designated areas.

“The local government chairman may not know the Fulani man in my village. But I know them and have enough time for us to interact. We have been able to make them see the need to live in peace,” Adole said.

So far, the Fulani have been cooperating with the Idoma leaders to maintain peace in the area.

“We wanted to continue to live in peace and do our business since most of us did not have anywhere else to go,” deputy leader of the Fulani herders in Otukpo, 43-year-old Abubakar Yau said.

Now the Fulani leaders have their own meeting on 28 of every month, discussing the latest development and the challenges they face in their various communities. Each time they identify any problems, they work out solutions before even bringing the matter to Idoma leaders.

Each time farmers complain about damage to farms by the cattle, Yau who has lived in Otukpo all his life said they do not argue with the farmers. “We let the guards know and together we go and see the extent of destruction and immediately resolve and pay damages,” he said.

Apart from the need to maintain peace, Yau said they cannot afford to keep paying the huge fines whenever the issues get to the state government.

“We have had to bail some of our people with as much as N700,000 and more. If you cannot pay, they come and carry your cattle, “he said. “That is what we are trying to avoid,'' he added.

A replicable peace model

Cletus Nwankwo, a lecturer at the Department of Geography, University of Nigeria, Nsukka (UNN), said that farmers and herders have, for the most part, enjoyed peaceful and cordial relations for many years in West Africa and other parts of the world.

“The Otukpo example is not isolated or peculiar,” he said. “There are peaceful relations between farmers and pastoralists in other parts of the country. Traditional mechanisms as seen in Otukpo and other mechanisms of conflict avoidance and mitigation are preferred by both herders and farmers.”

He noted that whether or not it can be replicated in communities that are hard hit by the crisis would be a matter of the communities' land tenure system and the code guiding social relations in different communities.

“Some communities do not allocate land to non-indigenes and talk more of guiding non-indigenous nomadic pastoralists to graze cattle like in Otukpo,” he said. “Thus, in advocating this kind of system, we have to recognise the difference in land tenure regimes and social codes of local communities across Nigeria.”

Nwankwo pointed out that many causes of the conflict must be recognised and not entirely be blamed on climate change and resource scarcity as the sole drivers of the clashes between farmers and herders.

The conflict must be first viewed in an individual local context, he said. Then consider how this local context is shaped by the broader social, economic and political settings of Nigeria and the West African region. Of particular importance is to discourage the use of firearms by pastoralists and farmers.

“Herders who voluntarily adopt ranching should be supported to practice this form of herding to reduce conflict”, Nwankwo said. “However, ranching should not be imposed and forced on the herders. Those who see the benefits and prefer ranching should be supported and helped to shift from their traditional nomadic system to this sedentary system.”

Rather than perceive nomads as uncivilised, Nwankwo argued that it is time to realise that they often operate at the margins because it is easier for them to evade taxes and other schemes of the modern society. “They are just rational actors who decide to dwell in a region where there is limited control and hindrance to their freedom.”

For Emmanuel Chiwetalu, a PhD student at Edinburgh University Divinity School, community leaders and individuals in affected communities can help to keep their environment safe, although Nigerian authorities have a major role to play in addressing this lingering conflict.

Chiwetalu, who is also a lecturer at the Department of Religion and Cultural Studies at UNN, however, pointed out that having a peaceful farmer-herder arrangement would require, among other things, the rejection of some of the suspicions and stereotypes that harm their relationship.

“Some of them are the idea that all Hausa and Fulani herders are seeking Islamic expansion; that they hate the Christian peoples in the middle belt and southern Nigeria; and that they are killers and nomads who do not value human life more than that of their cattle.”

He said that both the farmers and herders deserve to be treated as humans first, and then as Nigerians who deserve peace and prosperity and that to meet this obligation, both parties must sit at the communal level to reach an agreement on how to coexist.