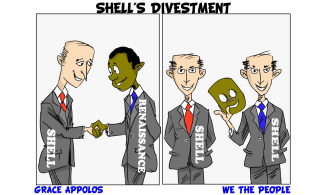

The uncanny relationship between Shell and Renaissance reinforces the growing feeling that Shell’s divestment of its Niger Delta oil operations is a grand disinformation smokescreen, carefully choreographed to disguise more sinister and profitable intentions.

On January 16, 2024, Shell announced through a statement on its website that it had reached an agreement to sell its Nigerian onshore subsidiary- Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Limited (SPDC)-, to a relatively unknown entity called Renaissance Africa Energy Company Limited. The statement brought to a close several months of speculation on the future of Shell in Nigeria, following the company’s 2021 announcement that it would be divesting all its onshore and shallow water assets in the country. The announcement was received with shock in the energy community, especially given the fact that more influential and financially capable companies had expressed interest in acquiring the assets Shell had put up for sale. More intriguing is the manner the sale was structured, including the concessions made by Shell to facilitate the purchase by Renaissance, and the influence Shell will continue to wield despite its rather loud ‘exit’ plans. The uncanny relationship between Shell and Renaissance reinforces the growing feeling that Shell’s divestment of its Niger Delta oil operations is a grand disinformation smokescreen, carefully choreographed to disguise more sinister and profitable intentions.

A Consortium of Shell ‘Old Boys’

Renaissance Africa Energy Company Limited is a consortium of 5 companies- ND Western, Aradel Energy, First E&P, Waltersmith and Petrolin. The company was legally registered in Nigeria on June 6, 2022, exactly 13 months after Shell announced it will be selling its Nigeria assets. Beyond the individual records of the consortium members, Renaissance has no record of ever carrying out a business transaction. In fact, the only news content on its website is the announcement that it had acquired SPDC’s assets. For some Nigeria energy experts, the manner of Renaissance’s emergence and rise is indicative that it was set up specifically to acquire the stakes of SPDC, and nothing else.

More revealing is the background of the leaders of Renaissance. 6 of the 8 listed members of Renaissance’s leadership are former Shell employees, some of them left only months before the formation of the company. Mr. Layi Fatona who represents Aradel Energy in the consortium spent seven years in the Petroleum Engineering and Exploration Department of Shell. Mr. Ademola Adeyemi-Bero spent 20 years at Shell and occupied several significant roles including Business Director, Board Executive of SPDC, Vice President of New Business Development in Africa within Shell International, etc. Mr. Gbite Falade was the Petroleum Economics Discipline & Portfolio Lead for Shell in Africa. Engr. Tony Attah who is the Managing Director/CEO of Renaissance, worked in Shell for over 30 years in various roles including as Shell’s representative at Nigeria’s Liquified Natural Gas Project, Managing Director of Shell Nigeria Offshore business (SNEPCo), Vice president for HR Sub Saharan Africa, Vice President for HSE and Corporate affairs within Shell and general management at the Technical level. He only retired from Shell in January 31st 2022 to take over the leadership of Renaissance. Bayo Bashir Ojulari who is the Executive Vice President of Renaissance was at Shell Nigeria Exploration and Production Company’s (SNEPCo). He was also previously General Manager Business and Government Relations at Shell. He may have only retired from Shell in June 2023. Mr. Eberechukwu Oji was in Shell for nearly 5 years where he held senior positions ranging from Manager, Maintenance & Integrity for Shell Companies in Nigeria and Asset Manager for the Central Hub. The entrenched affiliation of the leadership of Renaissance to Shell may explain why it was preferred in the sale, but it also throws up issues of transparency and conflict of interest which raises doubt about the entire process.

Who funds the purchase?

In 2021, analysts at Wood Mackenzie’s valued Shell’s assets put up for sale within Nigeria’s oil sector joint venture partnership at $2.3billion, and described it as ‘a challenging portfolio of swampy assets’. Several Nigerian oil companies expressed intention and presented bids to buy the assets. Bids closed on 10 June, 2022, just 4 days after Renaissance Africa Energy Company Limited was legally formed. 6 months after, the company was announced as the winner of the bid, outperforming several other well-established oil companies that were in the race.

According to the details of the transaction, Renaissance will pay Shell US$1.3 billion. Renaissance will also ‘make additional cash payments to Shell of up to US$1.1billion, ‘primarily relating to prior receivables and cash balances in the business, with the majority expected to be paid at completion of the transaction’. The transaction also says that Shell will provide Renaissance a loan of up to US$1.2billion, to cover a variety of funding requirements. In simple terms, out of the $1.3 billion first tranche payment Renaissance is expected to make to take over Shell’s asset, Shell will be loaning it $1.2 billion. Renaissance will only be expected to contribute $100 million. Evidently, Shell is purchasing its own assets. A key information missing from the details of the transaction is the terms of the loan agreement. For example, what are the considerations and terms of repayment? What is the expected duration of the loan, and what are the penalties in the case of default? These details are critical because it could shed light on how Shell may continue to benefit from the asset it claims to have divested.

How will Renaissance operate?

According to Shell, all of its employees would be kept on by Renaissance. It further says that the divestment transaction will preserve their operating capabilities within Nigeria’s oil sector joint venture arrangement, including ‘the technical expertise, management systems and processes that SPDC implements on behalf of all the companies in the SPDC Joint Venture (SPDC JV).” Again, in simple terms, Shell will continue being present and managing all the assets, including, managing Renaissance. The only difference is that the name of Shell will conveniently disappear and be replaced with Renaissance. Even though it claims to be selling those assets, Shell is tied to the same assets through interest on the loans and contingent payments.

Shell is essentially funding its own departure from onshore operations and keeping a financial stake in the result by lending money to Renaissance and keeping a role in the SPDC Joint Venture. Even with Renaissance at the helm, Shell stands to gain from the company's future success through interest payments on the loans, performance-based contingent payments, and other means. Through this arrangement, Shell is able to remove its name from day-to-day operations while remaining financially involved and perhaps making a profit. Shell avoids getting its hands dirty with the problems associated with onshore oil operations in Nigeria, like the increasing pressure from communities for restoration and reparations, while still protecting its financial interests through the loans and possible payments down the road. Shell appears to have discarded its Niger Delta portfolio and all the "headache" that comes with it, but in reality, it is still actively involved in the region and shares in every barrel of crude oil drilled from the area. This is all part of Shell's strategic approach; it optimizes its entire business strategy by effectively divesting while maintaining an income stream.

Dissociating itself from assets in the Niger Delta serves Shell’s overall interest in at least one more way. It allows the company lay claims to reducing greenhouse gas emissions while in reality, no emissions have been reduced. In its Energy Transition Strategy 2024, Shell reported that around 50% of its global routine and non-routine flaring in 2023 took place in Nigeria assets which it is planning to sell. In the report, Shell claims that it is ‘working to reduce routine flaring, which is inefficient and contributes to climate change” It says further that the company’s ‘target is to eliminate routine flaring from our upstream operations by 2025’. Shell adds that this emissions reduction target is ‘subject to the completion of the sale of SPDC’. Put simply, selling off high emitting assets in the Niger Delta for immediate and future profits, is how Shell intends to achieve net zero and lay claims to transitioning. Through divesting, Shell transfers emissions associated with its Niger Delta assets to Renaissance, and claim credits for reducing emissions, without actually turning off a single one of the hundreds of gas flare point it ignited decades ago.

Shell’s divestment in the Niger Delta is not merely misleading it is also a business and public image masterstroke. By divesting to Renaissance, the company maintains oversight and management of the same assets, retains its workforce, circumvents decommissioning expenses, mitigates the risk of escalating litigations, sidesteps compensation costs, avoids the remediation of historical pollution, and asserts its commitment to achieving emissions reduction and climate goals. It accomplishes all of this while simultaneously maintaining profitability from the same assets.

While the Nigerian regulatory body has rightly halted the sale to Renaissance on grounds of financial and technical competence, there is need to go far and beyond. It is important that all details of the transaction are made public, including details of Shell’s continued engagement in onshore oil assets, as well as the terms of the loan it is granting Renaissance. Also critical ahead of any planned divestment is a clear assessment of the environmental and human impacts of Shell’s extractive activities in the region, followed with a clear plan for addressing those outstanding concerns. Shell must also commit to decommissioning its assets through a valid financial instrument that covers the cost for doing so.