By Ayomide Eweje

Primary Healthcare Centres (PHCs) are developed and designed to serve as the first and most accessible point of care for thousands of families in Nigeria. They are meant to provide essential health services that should improve community health. Yet in Buruku LGA of Benue State, the reality inside these facilities falls far short of this mandate. Instead of functioning as the foundation of the local health system, many PHCs remain under-resourced, poorly equipped, and structurally unprepared to meet even basic health needs, especially for the most vulnerable groups.

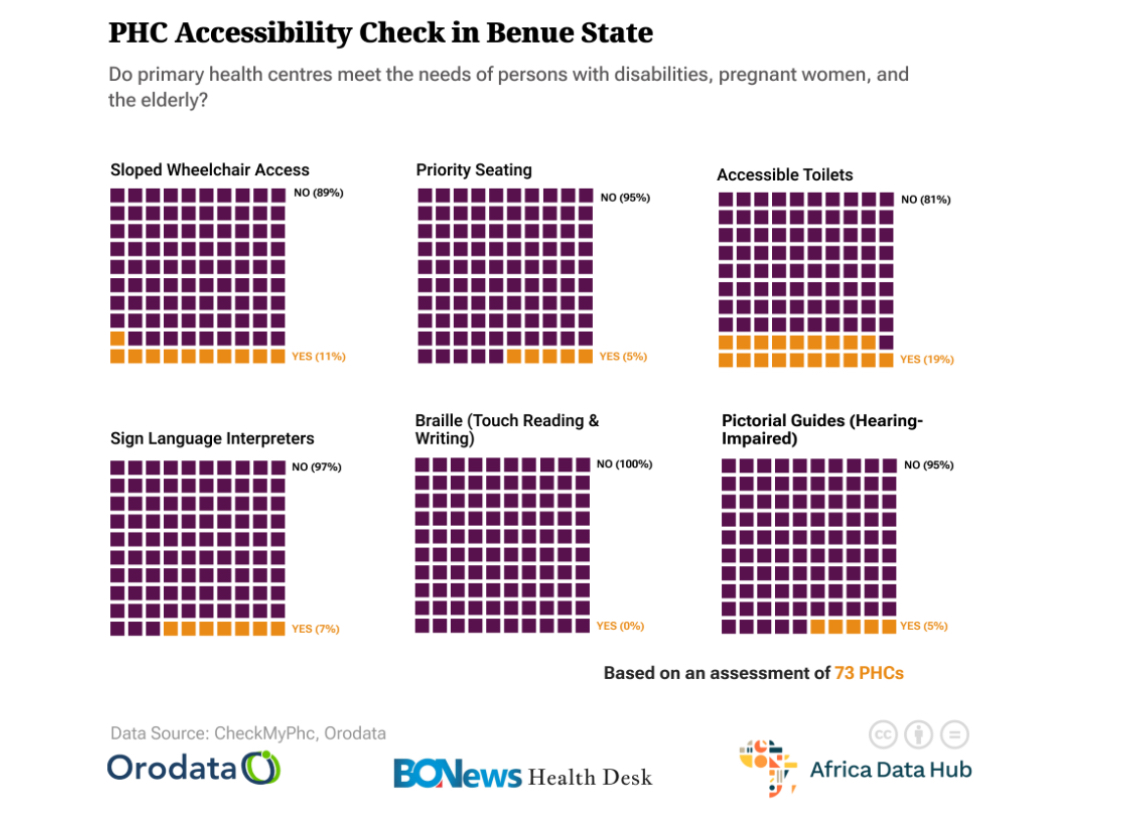

Facility-level data extracted from the CheckMyPHC platform developed by Orodata Science and corroborated with data from the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) reveal worrying gaps in Buruku’s PHCs, including electricity, water, delivery rooms, skilled birth attendants, functioning toilets, and basic equipment. Beyond these systemic gaps lies a more troubling trend, that is, the unintentional exclusion of persons with disabilities. These gaps create invisible but significant barriers for people with mobility, visual, or hearing impairments in accessing routine care, antenatal services, immunisation, and emergency treatment.

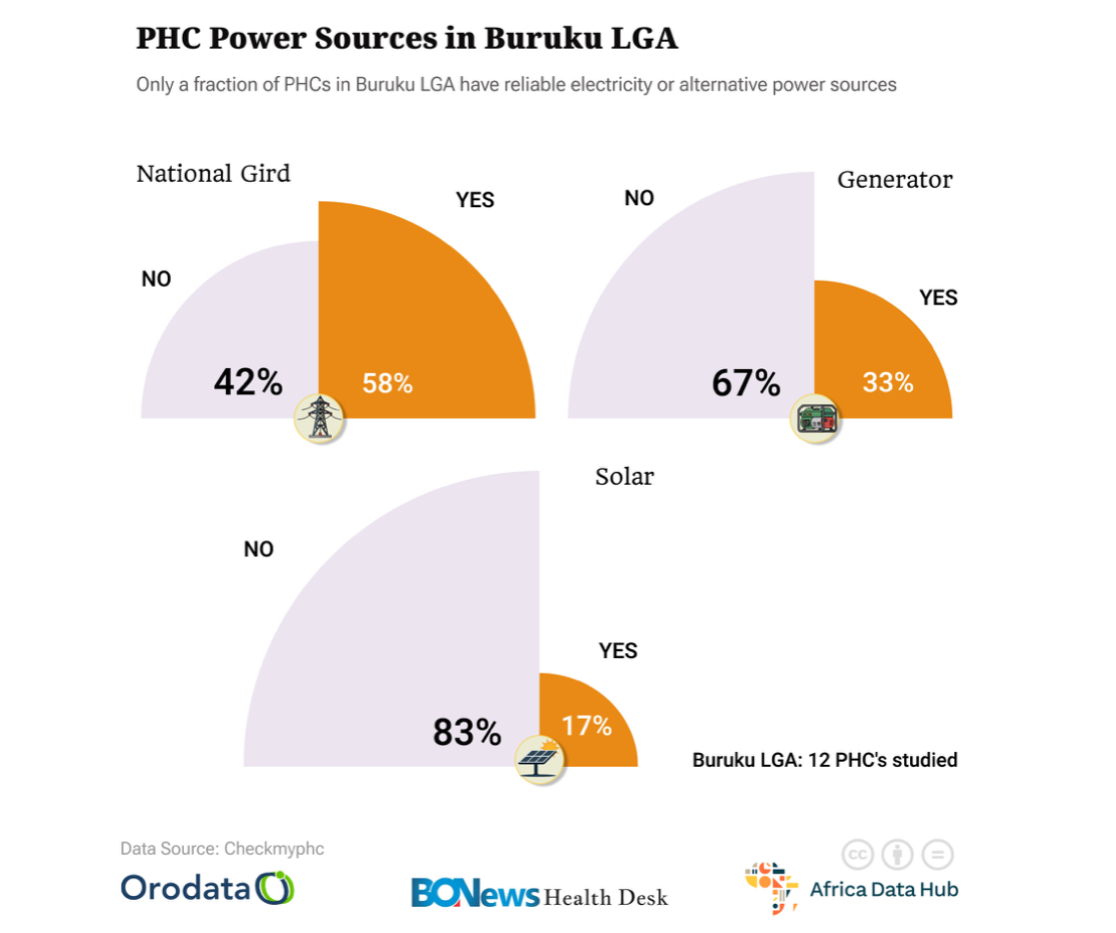

Across Buruku LGA, some PHCs still lack the basic utilities needed to deliver safe and reliable healthcare. Facility-level data on the CheckMyPhc platform shows that only a handful of PHCs, such as Adi, Mbagen, Apesough, Ako, Phc Anvambe, and Agwabi, have access to electricity via the National grid or solar power. Meanwhile, other PHCs, such as Uga PHC, rely on generators, while Adingi PHC has no power source at all. The NPHCDA platform corroborates this, noting that Adingi PHC uses rechargeable lanterns as its power source, which is detrimental to service delivery, especially during emergencies. The water supply is equally insufficient, as some facilities depend on alternative water sources, such as streams and underground wells, while only a few, including Mbagen and Apesough, operate with functional boreholes. These inadequacies affect infection control and the basic hygiene of patients and staff. More concerning is the fact that these utility gaps inconvenience health workers, fundamentally weaken service delivery, hinder safe childbirth, compromise vaccine storage, and leave routine and emergency care vulnerable to failure.

Meanwhile, the gaps in PHC functionality across the Buruku LGA extend beyond electricity and water; they also impact the very core of primary healthcare, including delivery rooms, skilled birth attendants, and essential medical equipment. NPHCDA data show that while a few facilities have designated delivery rooms, many are barely functional and lack essential equipment and supplies that would benefit mothers and newborns. Alarmingly, none of the reviewed PHCs have Skilled Birth Attendants (SBAs) on duty, leaving pregnant women at risk, especially during labour complications that require prompt intervention. Although data show that these PHCs need between two and four SBAs to operate effectively, they rely on Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs), a few nurses, and, in the case of Mbagen PHC, one doctor to serve the communities that rely on them.

Equipment shortages further deepen these vulnerabilities. Basic items such as delivery beds, sterilisation equipment, blood pressure monitors, cold-chain devices, and oxygen tanks are either unavailable or inadequate in multiple PHCs. These inadequacies compromise safe deliveries, limit antenatal and postnatal care, disrupt immunisation services, and weaken emergency response capacity, forcing PHCs to refer patients to nearby General Hospitals, with patients bearing transportation costs since none of the PHCs have ambulance services. Collectively, these shortages pose broader public health risks as they increase preventable deaths, lower community trust in PHCs, and widen the gap between rural households and essential healthcare in Buruku LGA.

While PHCs in the Buruku LGA continue to struggle with basic infrastructure, an equally critical but less visible gap lies in how the design and daily operation of these facilities unintentionally exclude persons with disabilities. Although neither the CheckMyPHC nor NPHCDA datasets directly assess accessibility features, patterns in terrain, building layout, staffing, and service availability reveal subtle but significant barriers that make it difficult for people with mobility, visual, or hearing impairments to access and use these facilities. From uneven, grassy, cobbled, or unpaved walkways to the absence of ramps and assistive communication tools and the lack of trained staff in disability-inclusive care, disability inclusion remains a neglected standard despite being essential to equitable primary healthcare. This invisible and silent form of exclusion means that even in communities where PHCs are technically functional, persons with disabilities are often physically or functionally shut out and unable to access the essential healthcare services they need fully.

Findings from the CheckMyPHC and NPHCDA assessments reveal that many PHCs in Buruku are already physically inaccessible even before a patient reaches the consultation room. Although several of the reviewed PHCs have constructed accessibility ramps, the terrain surrounding the facilities is uneven, characterised by grassy soil, cobbled walkways, and a complete absence of paved or stabilised pathways in most PHCs. For persons with mobility impairments, especially wheelchair users or those who rely on walking aids, these conditions turn a basic healthcare visit into a physical ordeal. The barriers continue at the building entrances. At Uga PHC, for instance, the sitting area is directly facing the ramp, making it difficult for wheelchair users to navigate their chairs and access healthcare. Phc Anvambe, on the other hand, only has a ramp in one building, despite the facility having several buildings. This inadequacy will frustrate mobility-impaired individuals when they attempt to access other buildings within the facility. These design limitations, though often overlooked and unintentional, create significant obstacles that effectively exclude persons with disabilities from receiving timely and dignified care.

Uga PHC- Front View. Source: NPHCDA

Another often-overlooked aspect of healthcare accessibility in Buruku is the unique barriers faced by people with visual or hearing impairments. All of the reviewed PHCs lack clear signage, adequate lighting, visual markers, or guides, making it difficult for individuals with low vision to navigate the facilities safely. Equally, people with hearing impairments receive little communication support, as none of the assessed PHCs have sign language interpreters, visual communication boards, or staff trained in alternative communication methods. These local barriers reflect national patterns highlighted by the World Bank’s Disability Inclusion in Nigeria: A Rapid Assessment(2018), pointing to inaccessible environments, weak disability-related training for health workers, and poor access to information and communication as major obstacles. The assessment further notes persistent negative attitudes among health workers, the absence of a disability focal point in the Federal Ministry of Health, and a lack of adequately funded inclusive policies, all of which ultimately shape what happens at the PHC level. As a result, persons with visual or hearing impairments experience a health system that is structurally unprepared to meet their needs, reinforcing exclusion even in facilities intended to serve the entire community.

In addition, beyond physical infrastructure, staffing and service availability play a critical role in determining whether primary healthcare is truly accessible for persons with disabilities in Buruku LGA. While staffing shortages affect all patients, their impact is disproportionately felt by those who require assistance, rely on predictable care schedules, or need service continuity. Emergencies further expose these gaps, as understaffed facilities struggle to provide timely responses, forcing referrals that require additional travel and expenses. In this way, everyday service inconsistencies quietly deepen exclusion, reinforcing a system in which access depends not only on proximity to a PHC but also on a patient’s physical ability, resources, and flexibility to navigate an unpredictable healthcare environment.

These findings reveal how gaps in infrastructure, staffing, and facility design in Buruku’s PHCs extend beyond operational weakness and inadequacies to become equity failures with real consequences for maternal and child health, disability inclusion, and grassroots healthcare access. When PHCs lack reliable utilities, skilled personnel, and inclusive design, they not only undermine safe childbirth, immunisation, and emergency care, but also systematically exclude persons with disabilities from services meant to serve entire communities. This weakness contradicts Nigeria’s commitments under Sustainable Development Goal 3, which emphasises equitable access to quality healthcare for all. Addressing these challenges will require targeted funding, inclusive facility planning, adequate staffing, routine maintenance, and stronger accountability at the local and state levels. Strengthening primary healthcare in Buruku and across Benue State means recognising that PHCs must be not only functional, but genuinely accessible to everyone who depends on them.