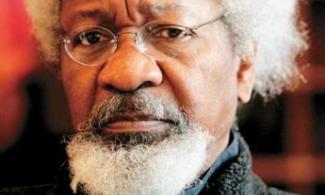

Abridged Lecture Delivered at the Wole Soyinka Centre, Lagos, 13 July, 2011 as part of Activities to Commemorate the 77th Birthday of Professor Wole Soyinka by Adebayo Olukoshi.

Abridged Lecture Delivered at the Wole Soyinka Centre, Lagos, 13 July, 2011 as part of Activities to Commemorate the 77th Birthday of Professor Wole Soyinka by Adebayo Olukoshi.

googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display('content1'); });

I feel highly honoured to be a speaker on this occasion of the 77th birthday of one of Professor Wole Soyinka and on the platform of the Soyinka Centre that is devoted to the worthy cause of investigative journalism. The life and example of Professor Soyinka has been an inspiration to at least three generations of Nigerians. I count myself among the legions of people in Nigeria, Africa and far beyond who have been inspired by him as much for the sheer power of his intellect and erudition as for the political commitments he has consistently stood for and the unalloyed courage he has always displayed – even in the face of personal danger.

As a student at Federal Government College, Sokoto, in the 1970s in what was then the Northwestern State, and which, after the subsequent creation of additional states in the Nigerian federation, came to be known as Sokoto State, my bosom friend, Akin Olaoye and I, among other peers, were fired by the breadth of Soyinka’s knowledge and the versatility he displayed in his scholarship. Our introduction to Soyinka’s wriotings came through the Trial of Brother Jero but once haven tasted of the power of his pen, there was no stopping us in terms of the range of writings that flowed from him which we tried to digest. So eager were we to be like Soyinka that we enthusiastically worked on a letter which Olaoye wrote out and sent to him, outlining the qualities we admired in him and seeking his advice on how we too could become like him.

The elation which Olaoye and I felt knew no limits when we got a short reply from Soyinka himself, signed personally by our legendary and incomparable hero himself! I know I was not the only one who memorized the reply and recited it as often as the opportunity arose. But that was when the post office still worked as an important institution in the community and a key instrument in the effort to build solid bridges across the Niger and Benue in all directions. It was also the time when the investment in the educational sector by state and society was considered as a matter of priority, complete with efforts at building a curriculum that could contribute to the strengthening of civic identities and a sense of personal dignity.

When, after my first degree at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, the time came for me to choose a school to go to for my postgraduate studies, Leeds University was a natural choice for me - for Soyinka had been there and I stated so in my application papers as one of the motivations for my choice. Although the topic of my doctoral research was industrialization in Africa and the primary department within which I was to undertake my advanced studies was Politics, one of the first places I visited was the Leeds theatre studies Department where I had tea with a most welcoming Martin Banham, Director the Theatre Studies programme, who remembered Soyinka well with the pride that only experienced teachers are capable of displaying, and lapped up his words of encouragement on how the Soyinka example could be emulated.

I have gone into some of these personal reminiscences principally to underscore a point which is relevant to us today as a nation and to this assembly that has congregated to re-evaluate local governance in Nigeria. The point I seek to underscore is that no nation can thrive and prosper without public figures whose lives and examples sum up the ideals that its citizens seek to uphold in the onerous task of state and nation-building. In so doing, those figures become examples for others to emulate, reproducing the high ideals and values by which great nations make and remake themselves in an unending flow of history. My generation is fortunate – and I consider myself singularly lucky - to have the likes of Soyinka, Achebe, and other men and women of letters as standard bearers of the Nigerian, pan-African and humanistic ideal from whom we could draw inspiration and who, unknown to them, helped by their work to shape our future by the path they had trodden, by their challenge to us to dream dreams of a tomorrow in which Africans and all peoples of African descent will find their rightful place in the comity of nations.

Democracy is an ideal and the core values that underpin it are universal. However, it is the actions of people, organized as citizens, that make the democratic ideal a living and on-going experience that unfolds from generation to generation, propelled, to paraphrase Frantz Fanon, by the discovery which each generation must make of the historic mission that it must fulfill or betray. It is the combination of individual and group action that makes democratic change in the quest for the ideal of democratic development possible.

The basic role and place of the media in the democracy project is now well-established in theory and practice to merit any extensive discussion here. Alfred Opubor and his colleagues in Lagos and elsewhere have devoted a part of their investments in the building of mass communications research and training in this part of the world to underscoring the essential duty of the media in the promotion of civic identities and democratic governance. What is important to keep in mind today, in the framework of our reflection on local governance, is the question of the combination of tools and methods by which the media might play its role in a robust and effective manner as to contribute to the deepening of the roots of democracy and the extension of its branches. This is by no means an easy question. Indeed, arguably, it is a question for which no fully satisfactory answer has been found in the praxis of democracy-building itself. Nevertheless, there is a broadly shared agreement that the investigative culture and capacity of the media are central to its ability to play its role in helping to assure that systems and processes of governance are not only representative of the citizenry but also accountable to it and participatory.

Investigative journalism is a powerful tool of governance precisely because in holding power accountable and keeping it constantly reminded that sovereignty belongs to the people, it is both a tool of empowerment of the self and others - and a very risky enterprise. I submit that no democracy can be considered to be healthy which does not have a robust culture of investigative journalism built into its media landscape. In holding power accountable, investigative journalism also empowers the citizenry, nourishes the public policy process, and complements other forms of citizen action to make the democratic ideal a living, everyday experience.

The history of the quest for effective and participatory local governance in Nigeria is as old as the history of political communities in the area that came to be constituted in 1914 into the country we know today. Political communities, understood as an aggregation of people organized into a recognizable or defined geographical space within which structured authority is legitimately exercised, have existed in the Nigeria area for centuries, comprising an admixture of republics, city-states, kingdoms and empires with fairly differing structures of power that range from the most basic to the most elaborate. A generation of nationalist historians, a significant proportion of them congregated in the old Ibadan School of History, has bequeathed us with rich accounts of the making, consolidation, dissolution and renewal of these political communities as part of the battle which it waged against an earlier racist colonial historiography that claimed that Africa had no history – at least not any that is worthy of note – before the arrival of the white man on the continent.

A careful and critical reading of the historical accounts on the nature and workings of the old-established political communities that existed in the Nigeria area would suggest clearly that:

a) The state system is as organic to the African world as it was to other regions;

b) The history of the state system long predates the arrival of the first Europeans

to the African continent;

c) A system of local governance was integral to the organization of power and

structuring of decision-making, and this was as true for centralized political

systems as for decentralized ones;

d) Local governance played a central role in the mobilization of legitimacy for rulers and the generation of consent from those whom they ruled, including among groups that were initially forcefully integrated into a political community by war and conquest;

e) The depth of local governance and the extent to which it was representative of local communities was integral to the overall unity and integrity of political communities; and

f) The objectives of the devolution of responsibility – and the powers that correspond – as part of a strategy of local governance were multiple and included the establishment of a pan-territorial presence, the cultivation of legitimacy, and the generation of consent.

On the face of things, following the onset of colonial rule, the logic of consent and legitimacy that was built into local governance appeared to have been maintained by the new imperial authorities. However, the principle underpinning local governance in the colonial administrative system represented a radical departure from the pre-colonial experience. The blueprint for colonially-sanctioned local governance was laid out in Frederick Lugard’s Dual Mandate and the principle of Indirect Rule around which his thinking was built. Indirect Rule had been tried out in India prior to its importation to Africa where Nigeria served as a prime site for its application. The Indirect Rule system purported, in effect, to leave the pre-colonial structure of authority more or less intact under the “protection” and oversight of the colonizing power. It was out of this system that the colonial native authorities within which “traditional”/ “natural rulers” exercised authority in the name of the colonial power was created. Indeed, over the period leading up the amalgamation of 1914 to the 1930s, “traditional” rulers in fact functioned as (sole) native authorities. It was only subsequently, during the 1930s and 1940s, that the notion of the chief-in-council was introduced.

The theory of Indirect Rule might have proclaimed the existence and exercise of a dual mandate in the exercise of colonial affairs. In practice, however, Indirect Rule and the local governance sub-structure that was built into it represented one of the most repressive experiences of administration in Nigeria’s history. The reasons are many and can be summarized as follows:

a) Given the colonial foundational structure on which it was erected, it served as a means for the extraction of taxation and other revenues without offering any possibility of representation for the “natives”. Indeed, the “natives” were legally defined as the subjects of a foreign sovereign;

b) The notion of “native law and customs” that underpinned the Indirect Rule system was a stylized one which removed checks and balances in traditional authority systems such as they existed and disproportionately concentrated power in the hands of chiefs who were effectively reduced to local colonial enforcers. Where authority did not previously reside with a symbolic chiefly figure, the colonial authorities did not hesitate to invent them along with corresponding traditions;

c) A local policing service was introduced to accompany traditional authority in the enforcement of the new colonial administrative and fiscal order; its work was reinforced by a court system that was as renowned as the native authority police for its oppressiveness; and

d) The subjection of whole swathes of the “native” population, particularly those in the rural area to customary as distinct from civil law, with implications for access to the basic civic liberties which citizens ordinarily ought to take for granted.

It is little wonder then that Mahmood Mamdani, taking stock of the experience of local governance during the colonial period, characterized it as an exercise in decentralized despotism operationalized within the framework of a bifurcated state that erected its own Wall of China between the civic and the customary the better to dominate the colonized. Peter Ekeh was to point to the long-term alienating effects of the colonial governance model and its legacy of two publics, the one civic, the other primordial. Franz Fanon, Amilcar Cabral and other thinkers similarly pointed to the alienating effects of colonial rule both generally and with specific reference to its approach to local governance that produced an admixture of declasses and deracines.

Resistance to decentralized despotism was widespread across colonial Nigeria and took various forms, including immediate violent rejection, sporadic uprisings, and mass migrations. It constituted a recurrent feature of colonial rule and was witnessed in all parts of the country. Some of the better known episodes include the Satiru uprising, the Egba protests, and the Aba Women’s “riot”. In time, the pressures arising from domestic resistance to the colonial system of local governance translated into a concerted nationalist anti-colonial movement which gathered steam after the Second World War. The bid to manage, even contain the growing tide of anti-colonial nationalism resulted in the establishment of a number of commissions aimed at effecting legal-administrative reforms that will increase the “native” voice in the overall administration of local affairs. In this connection, elections were organized in the late colonial period in which natives were allowed to participate. These elections were mainly held over the period between 1950 and 1955 in Lagos, and the Eastern and Western regions; change, such as it was conceived came more slowly to the Northern Region. The various reforms were, however, too little, too late; the train of independence had become unstoppable.

Looking back on the 50 years since Nigeria’s independence in 1960, it can be convincingly argued that one of the dominant themes in the post-colonial agenda of politics and policy-making is the reform of local governance. Through the various shifts that have occurred in the structure of the Nigerian federation over the years, the changes in the balance of power among the tiers of government in the federal system, and the impact which prolonged military rule had on national-territorial administration to the various efforts at post-independence constitution-making, the emergence of the oil economy and its impact on revenue generation and allocation, the role and place of local administration in the overall architecture of post-colonial governance has been marked by twists and turns that could be said to comprise an admixture of progress and regression.

Scholars ranging from Billy Dudley, Oyeleye Oyediran, Ladipo Adamolekun, Alex Gboyega, and A.D. Yahaya to Dele Olowu, A.Y. Abdullahi, G.O. Orewa, Akinyemi Savage, and Otive Igbuzor, to cite a few of them, have metioculously chronicled and analysed the weight of the various reforms, direct and incidental, which were carried out during the lead up independence and in the years since then. The 1976 local government reforms pronounced by the Murtala-Obasanjo military administration and the subsequent debates on local governance that took place in the Constituent Assembly that drafted the constitution for the Nigerian Second Republic; the integration of the principle of elected local government into the 1979 constitution; the 1992 decision by the Babangida military administration to abolish ministries of local government, make direct resource allocations to local governments, and introduce the principle of the separation of executive and legislative functions at the local level; the 1998 nation-wide elections held into the 774 local government councils as part of the lead-up to the inauguration of the Nigerian Fourth Republic in May 1999; and the 2003 Sanda Ndayako Commission on Local Government Administration enabled by the Council of state have all been captured in the literature as representing some of the most significant – though not necessarily decisive - developments in the post-colonial quest for a more effective system of local governance.

There is a broad agreement among the leading scholars that in spite of all the efforts that have been deployed, Nigerians are still an appreciable distance away from enjoying the ideal of a system of local governance that is:

a) An integral and substantive part of the social contract that frames the rights, entitlements, privileges, duties and responsibilities of the Nigerian citizen;

b) Representative of the citizenry as individuals and communities;

c) Participatory in a manner that ensures the active input of the populace in the exercise of policy choices and the making of decisions;

d) Accountable to the citizenry both in the technical and political senses;

e) Empowered to be a legitimate driver in the national development project; and

f) A site for the pursuit of everyday democracy.

Oyeleye Oyediran captured the mood of most students of the Nigerian local governance system when he observed that all of the efforts at reform had helped the country to sight Canaan but the road ahead to the desired destination was still long and treacherous to a point where it could not be taken for granted that it will be reached. Why has this been so? The explanations that have been proffered in the literature are many and varied. They include the:

a) Failure of post-independence governments to depart radically from the colonial logic of local administration;

b) Adverse impact of prolonged military rule on the Nigerian federal system, including the over-centralization and concentration of power in the federal centre;

c) Flip-flops in policy and orientation, including a rapid turnover and inconsistency, that is both reflective of the chronic instability of the Nigerian political system and is destabilizing of local administration;

d) Absence of substantive autonomy for local governments, and their effective subordination to other tiers of government within an overall structure of power that consigns them to a residual position;

e) Inadequacy of mechanisms of accountability in the local governance system through which officials could be held responsible by citizens for their performance;

f) Ambiguities in the 1999 constitution with regard to the functioning of the local government system;

g) Widespread corruption that takes place in the local government system; and

h) Non-viability of most local governments as autonomous economic units, including their low internal revenue base and near-total dependence on statutory federal allocations.

The various explanations that have been advanced for the inability of local governance in Nigeria to fulfill its potentialities and promise to the full are not individually and collectively without an element of validity to them. However, they appear to be partial in some cases and simply symptomatic of larger problems in a number of others. To come to grips with the crisis of local governance in Nigeria such as it has been expressed in the many of the studies that have been carried out, it will be necessary to revisit the entire project of post-colonial state and nation-building with a view to imbuing with a coherent, clear and comprehensive vision of democracy and development in which the citizen is at the centre and the community constitutes a prime building block. Democratic governance is propelled by active and empowered citizens and their communities.

Across the Nigerian political system, the case for taking local governance much more seriously as the bedrock of quest for democratization at the national level can be hinged on the following arguments:

a) It could allow for deeper grassroots participation in the administration of the affairs of the community;

b) It serves as a veritable breeding and training ground for future leaders to cut their teeth before going onto to the national stage – and beyond;

googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display('content2'); });

c) It offers a viable and sensible framework for citizens to enjoy the benefits of democracy first hand, including the efficient supply of various socio-economic dividends;

d) It could provide a foundational platform for exacting accountability from public officials and political office holders;

e) It is the primary site at which a new social bargain between the Nigerian state and the citizenry must begin to negotiated; and

f) It is the layer of governance that touches or has the potentiality to touch all citizens and, to that extent, it is the site where the quality, relevance, and even long-term health of the democratic system can be effectively experienced and assessed.

The importance of the media in the struggle which must be waged in all contexts of democratic transition cannot be over-emphasized. Of particular importance here is the role which the media itself could play directly through investigative journalism. But also critical is the necessity for the media to give visibility and voice to local communities through the reporting of their concerns and, where viable, the opening up of opportunities for community journalism. An investigative media anchored in the aspiration of communities for a system of governance that is democratic and developmental is a prerequisite for the flowering of an active citizenship and an enabler of everyday democracy.

Adebayo Olukoshi-UN African Institute for Economic Development and Planning (IDEP),

Dakar, Senegal.

googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display('comments'); });