As we mourn the passing of a great African intellectual, Prof. Ali Mazrui, I present to you a 2007 dispatch from Christopher Okigbo International Conference at Harvard University. Before then, I had met and interviewed Professor Mazrui twice. But on that day, I saw an Ali Mazrui that I had never seen before.

Kwaheri, Mazrui arap Mombasa.

You reached your destination-

A thousand miles beyond the boundary.

I was a witness.

Now, you’ve set forth

On a trip across the sacred cloud.

Sorry, I couldn’t deliver

"The Trial of Ali Mazrui"

Before the bracket closed.

But you can be sure

It has set sail,

Far beyond the bondage

Of our triple heritage.

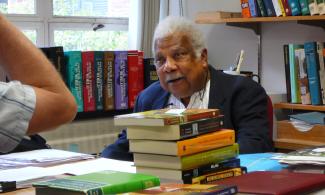

As we mourn the passing of a great African intellectual, Prof. Ali Mazrui, I present to you a 2007 dispatch from Christopher Okigbo International Conference at Harvard University.

Before then, I had met and interviewed Professor Mazrui twice. But on that day, I saw an Ali Mazrui that I had never seen before.

For many scholars of African literature, Ali Mazrui was an outsider who crashed into the African literature party on the wings of Christopher Okigbo. His one and only novel, “The Trial of Christopher Okigbo,” made him a factor in literary discourse.

With notoriety comes despise. Mazrui is so despised that more scholars are not on talking terms with him than those who are.

But Mazrui, Albert Schweitzer Professor in the Humanities at Binghamton University, New York, continues to solider on. He fights hard to keep himself relevant. And he seems to be enjoying the attention.

It was not a wonder that he was featured at the Okigbo International Conference as a keynote speaker on Saturday, September 22, 2007. In an event billed to celebrate the life of the fallen poet, Mazrui played the role of the man brought in to present an opposing view critical of the poet for daring to die fighting for Biafra.

To some, Mazrui is a devil's advocate. But to others, he is the devil himself.

Mazrui knew this and began his speech with an appeal to people to hear him out because he was going to say things controversial. For scholars familiar with the place of opposing views in literary life, Mazrui was indulged. If some were preparing to pounce on him after his speech, it was not to happen for the man broke down in tears.

These are the things we learnt from Mazrui's presentation:

Ali Mazrui was on the side of the federal government during the Biafran war. He said that he wrote the novel, “The Trial of Christopher Okigbo” as a tribute to a martyr who died for a cause he, Mazrui, did not believe in.

According to Mazrui, he was at the brink of a nervous break down following the death of his friend when he wrote the novel. "It was private anguish, publicized," he said. "It was the first time I consulted a psychotherapist."

He said he chose to engage the poet in fiction because in his Swahili culture great moments of anguish are reflected in poetry. He gave an example of when his two children went blind and he received poems from his compatriots.

When Mazrui submitted the manuscript to Chinua Achebe, who was the editor of Heinemann's African Writers Series, he wondered if Achebe would "recognize the hostility to Biafra and my love for the Igbo."

Achebe, he noted, rose to the occasion when he accepted the manuscript. Achebe told him the novel started very slowly and asked him to get rid of the early part. Those Mazrui said were written "in the grip of my deepest psychological stress."

In the novel, Mazrui found those who opposed Biafra ‘not guilty.' He found those non-Igbo who supported Biafra ‘guilty.' As for the Igbo, he declared the charges against them ‘not proved.'

In his paper, “The Muse and the Martyr in Africa's Experience: Christopher Okigbo in Comparative Perspective," Mazrui accused Okigbo of subordinating his genius to parochial goals by acting as an Igbo first and a poet second. "Did Okigbo sacrifice the universality of his genius to his parochial interest?" he asked. He described Okigbo's poetry as "the voice of universality heard from a village boy." Okigbo's death, Mazrui said, was "a case of promise cut short. A symphony interrupted."

Mazrui mused that, "if he (Okigbo) had continued to write as he did and lived to be 80, he would have been a good poet, a brilliant one, but not immortal. If he had lived to be 80, he would have beaten Wole Soyinka to the Nobel Prize but he would not have been recognized amongst the immortal."

Then he submitted that "violent death is a path to immortality." Okigbo's beauty he stated was "beauty that death enhanced."

Mazrui recognized that Okigbo's death raised wider questions about justice. But he believed that such questions should be subjugated to the mission of the individual. He asked, "Should a gifted human being have a right to sacrifice himself?" He then concluded that, "all lives are sacred but some are more sacred than others."

When not lost in what has been called ‘the understanding of his confusion,' Mazrui appeared ‘lost in the confusion of his understanding.' On one hand, he questioned why Okigbo who rejected the first African poetry award at Dakar's Festival of Arts and Culture because he considered himself a universal poet and not an African poet, would pick up arms for Biafra. On the other hand, he questioned the concept of the European nation state handed down to Africans. "Political Africa," he said, "has been in denial of the tribality of its essence."

He called Nigeria "a work of art in painful progress." Okigbo's martyrdom he said, "is a challenge to Africa to explore a better alternative. "If he (Okigbo) had survived

Biafra, Mazrui wondered, "would he have been an anti-war poet?"

Then, Mazrui, the professor of political science, African studies and philosophy, interpretation and culture, paused. "I will now have a word with Chris," he said, as he rounded up his speech. "you may eavesdrop if you wish."

He cleared his throat and began:

"Chris, the same forces of violence which killed you in the war front on October 1967 killed my future father-in-law in the anti-Igbo pogrom almost a year before you were killed."

Then his voice began to break until it totally cracked up. For few minutes, he sobbed.

Thompson Hall was calm like a frozen anthill. "I'll be okay," he said as he took time to gather himself.

"Your poem is not finished, Christopher," he concluded. "Your poem is not finished. You are awake in the altar today."