Workers at the Tai Solarin College of Education are currently owed billions in salary arrears and unremitted cooperative and pension deductions by their employer-Ogun State government, from 2009 till date. Over the years, 48 of them have passed away in active service, with most of the deaths attributable to the hardship caused by the prolonged non-payment. In this three-part report, The ICIR‘s ‘Kunle ADEBAJO chronicles the challenges faced by the deceased before they died, and the frustration of the living college’s staff members as well as their dependants.

THE weather condition on a July morning at Ijebu-Ode in Ogun State was sunny, cloudy, and mildly windy. It was fair weather, and everything else seemed normal.

Students and teachers at Ijebu-Ode Grammar School including the visitors walked in different paces into the school premises. But not too far into the morning, the atmosphere changed abruptly from calm to commotion with the shocking discovery of a dead body.

A 66-year-old man, Abiodun Osinaike, who had worked at Tai Solarin College of Education, TASCE, until his retirement in 2017 was found lifeless behind the wheels of his beige-coloured 2001 Nissan Pathfinder.

Finding him at the location was no surprise. For years, the deceased had paid frequent visits to the premises of Ijebu-Ode Grammar School to participate in the annual marking exercises of the West African Examinations Council and the National Examination Council.

Though a former chief lecturer, head of the Department of Chemistry, and dean of the School of Science at the college, Osinaike could barely afford to feed his wife and three children because of the protracted non-payment of salaries by his employer, the Ogun State government.

To make ends meet, he joined members of the National Youth Service Corps, young graduates and secondary school teachers who earned paltry wages from marking answer scripts for ordinary level examinations. He also wrote science textbooks, which he marketed to schools.

Mojisola, Osinaike’s wife who taught at Christ Apostolic Church in Degun, had always relieved him of many of his financial burdens. But on August 22 2012, she had an asthma attack and was admitted at the Ogun State University Teaching Hospital. Three Wednesdays later, she died—despite a loan obtained by her husband from Guaranty Trust Bank to prevent her death.

“Ever since she died, things have been very tough for him,” says Titilayo Modupe, 34, Osinaike’s eldest child.

She recalls her dad slipping continuously into despair and needing to be constantly consoled. He was overwhelmed with worry, gloom, and financial burden. Titilayo is certain her father died of depression.

Her father’s misfortune was not unexpected, she said. The Ogun State government had owed him full salaries for over two years, part salaries for over four years, as well as pension arrears among other entitlements.

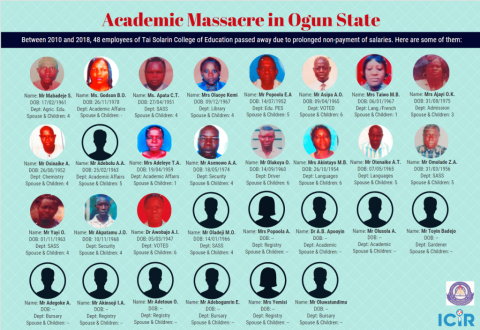

And all the over 300 individuals still working at the Tai Solarin College of Education (TASCE) are similarly affected. At the last count, other 48 former staff of TASCE have died in active service—the deaths of most of whom may be directly attributed to privation and depression.

There are 89 colleges of education in Nigeria approved by the National Commission for Colleges of Education, NCCE. Of these, three are situated in Ogun State, and TASCE is the only one owned by the state government.

First established in 1978 as the Ogun State College of Education, TASCE was upgraded to a university of education in 2005 after approval by the Nigerian Universities Commission. Then in October 2008, the college was disjointed from the university and relocated from Ijagun to a new campus in Omu-Ijebu. This separation commonly referred to as ‘disarticulation’ began the misfortune of the college workers.

In 1999, after its accreditation exercise, the NCCE rated TASCE as the best state College of Education. Over the last decade, however, the institution’s rating has dropped.

Life without a father, mother, or job

Since the death of both parents, staying heads above water has been tough for Titilayo and her orphaned brothers: Muyiwa and Michael. Life would have been more difficult had her dad not built a house of his own before the change of fortune. She imagines they would have ended up homeless or at best as beggars, having received very little help from relatives.

At their residence on Femi Ogunade Street, Irewon, Ijebu-Ode, Titilayo flips through a set of documents belonging to her parents as she narrates her family’s ordeal. One of those documents is her dad’s payslip from June 2010. Despite a total earning of N206,492, it shows that he was only entitled to receive N33,606—after numerous deductions, including loan refunds, which were not remitted to the cooperative society’s accounts.

The three children have not been able to get either of their parents’ entitlements from the state government. The eldest daughter discloses that while all the requirements for their mother have been satisfied, there is some difficulty getting access to some of their dad’s documents, such as specific payslips and letter of employment.

Suddenly becoming the family’s breadwinner has not been easy for Titilayo as she has been mostly without a job since she graduated from the Olabisi Onabanjo University’s Industrial and Labour Relations Department in 2011. Last year, she was employed as a supervisor by a private company based in Lagos, but was fired after excusing herself for two weeks to make arrangements for her dad’s funeral.

Now they depend on returns from her petty soft drink business and the meagre salary of Muyiwa who works with a small-scale enterprise in the town. Yet their joint earnings aren’t enough to cater for the academic needs of Michael, the youngest one who studies Entrepreneurship at the Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta.

“We don’t have means to pay his house rent and school fees once they call off the strike,” says desolate Titilayo as she flings her arms, “but we are still hoping on God that he will surely do something for us.”

Left in the lurch

The administration of Governor Ibikunle Amosun often touts itself as a respecter of the dignity of labour and one that is committed to paying workers’ salaries on time. But this claim comes to question when put against the fact that workers of TASCE are left without pay for many years.

For that long, staff members of the college haven’t been paid their full salaries among other entitlements — starting from the Gbenga Daniel-led administration and now the Ibikunle Amosun-led government, despite the current administration collecting at least three tranches of bail-out fund of N22 billion and being entitled to the last tranche of N17.3 billion. It is also in spite of the state generating the 3rd highest internal revenue in the country and the 7th highest total revenue. In the past seven and a half years, Amosun’s administration has also not paid its part of the contributory pension scheme.

All appeals made to the state governor, including getting highly respected indigenes of the state—such as former president Olusegun Obasanjo, Wole Soyinka, Bola Ajibola—as well as traditional and religious councils to lobby, have so far went to nought. The government, according to public records, owes up to N4.3 billion in Consolidated Tertiary Institutions Salary Structure (CTISS) and Consolidated University Academic Salary Structure (CUASS) arrears for the period of July 2009 to December 2018.

The situation is worsened by the school’s very little internally generated revenue and alleged mismanagement of funds by the college provost, Adeola Kiadese, and acting bursar, Gbenga Olusanya.

Amosun has claimed that salaries were not paid because the list of staff submitted to the government doubles the stated population of students, which he put at 3,000 workers to 1,600 students. But this has been denied by workers. Instead, they say the institution had 442 staffers in 2008 when it was disarticulated, while it presently has 349 workers (180 of whom are lecturers) and 3,690 students in all. The claim of the staff has been confirmed recently by the secretary to the state government, Taiwo Adeoluwa.

The infrequent payment of salaries has affected many households, none yet to receive the entitlements due to them despite fulfilling stated requirements. One of those households is the family of Popoola Adeoye Ebenezer, a senior staff member who died on March 18, 2013, as a result of lung cancer. He was operated at the University College Hospital, Ibadan, but could not follow through with the prescribed chemotherapy sessions. His request for financial assistance from the college management to fund this was not granted.

His wife, Popoola Abolade Iyabode, 55, who teaches at the Tai Solarin University of Education Primary School, now relies on her meagre salary and assistance from colleagues to keep the family going, including three children Popoola left behind.

There is also the family of Toyin Badejo, who worked at the college as a gardener before his death in 2012, following his involvement in a road accident on his way to work. His wife, Yemisi, whom he married in 1998, says she is 33 years old, but looks at least ten years older. Since her husband’s death, she has been catering for the three children by offering to assist well-to-do families with laundry and other house chores.

In 2017, her former landlord asked her to evacuate after owing months of rent, at the rate of N2000 per month. Where she presently lives with her daughter, Funmilayo, in the less accessible parts of Onirugba, Ijebu-Ode, Toyin pays N1500 every month. Dare, her first-born graduated from Government Technical College in 2016, but has not been able to proceed to a tertiary institution. In the mean time, he is apprenticed to a barber in Ago-Iwoye. Funmilayo, also a high school graduate, is learning tailoring till there is enough to send her to the university; and Titi, the last born was sent to live with a relative just to reduce the number of mouths to be fed.

A pension fund administrator at Pensions Alliance Limited, Wale Sodimu, explains that private companies that administer pension funds (PFAs) often pay retirees their deductions within 21 working days of receiving a response from the employer. The retirees are to submit their retirement letter, passport photographs, proof of age and means of identification, but if they are deceased then the next of kin has to visit the PFA for access to the funds.

Sodimu adds that, though he cannot speak on why government may be to slow to keep its end of the bargain, the bureaucracies and inefficiencies often associated with public offices do not characterise the private sector.

Meanwhile, Daniel Aborisade, chairman of the Coalition of TASCE Staff, says union members have been called a lot of times to accompany families of deceased workers to the pension office in Abeokuta, but they are always deluged with finicky requirements. The office also capitalises on monies owed to cooperative societies and requests that the debts be firstly resolved.

“I say how much are they owing. If someone is owing N700,000 at the cooperative, and you are owing that person almost N17 million, why can’t you deduct from source and pay the remaining?” Aborisade wonders. “But everything still boils down to the fact that government is not interested in staff welfare. Government doesn’t want to pay. They are not paying those of us who are alive. So they will not want to pay the families of the deceased.”

The burden of educating a fatherless trio

One prominent thing about the bereaved is their ability to remember exactly what day their loved ones died, regardless of how old the event. For Bukola, 40, the wife of late Adeyemi Adekunle Asenowo who worked at TASCE as a security operative for ten years, the date that sticks is Saturday, February 1, 2014.

Asenowo had been working for the learning institution since 2004. One day in 2012, while returning home from work, he was involved in a road accident close to Ijebu-Ode which damaged bones on his left arm. Knowing the school’s cooperative society lacked money to entertain loan requests, he wrote to the management for a salary advance to undergo surgery. But his request was denied, ostensibly due to a shortage of funds. Two years later, he passed away, his body sent to Ijebu-Igbo, a neighbouring community, for burial.

Even before his death, Asenowo’s family struggled to cater for basic needs, including square meals. He always complained about not receiving salaries, and whenever he received little payments they went into transporting him to and from work. Bukola, inevitably, learnt very early to be the family’s financial cornerstone.

Despite preparing and submitting documents asked of her, she has not received any benefits from the school or government, and has since resigned to fate—anticipating the day her children will become self-sufficient.

Bukola had three children for Asenowo: Fowowe, 12, Martins Fowosere, 10, and Fowoke, 8. The eldest two are enrolled at St. Anthony Primary School, and their mom is worried about expenses for their continuous schooling. “Everything is in God’s hands,” she concludes, after letting out a hollow, bitter laugh.

Martins, she observes, has shown himself to be exceptional brilliant, such that his teachers decided that he should skip primary five. His dad had fondly called him ‘doctor’, kindling in him a strong interest in a career in medicine. On the other hand, his elder brother has decided to become an engineer.

“Their dad had always called the youngest Fowoke [one who blesses another with money], but he did not wait around to live out the name,” says Bukola with a drawn face as she clutches her measuring tape.

Proceeds from her tailoring business, “God’s Times is the Best Fashion Designer”, are evidently not enough to see her three children through schooling among other crucial expenses. What’s more, she has received no financial help from relatives and has been managing on her own.

“There is nothing left to be said except that the government should help us… because the children are still small and still have a long way to go. If they can have mercy on us… because… not up to two years after his death, his family asked me to remarry,” she says, contagious tears beginning to swell up. “But which man do I want to give three children? Those who have not even borne their own burdens successfully?

“I will be glad if the government can help… for the sake of my children’s education.”

A widow’s curse

According to many cultures, curses uttered by the oppressed are more likely to be fulfilled compared to those from ordinary men. Certain tribes in Nigeria further attach special weight to harsh prayers made by widows. Perhaps Bukola Babatunde,* 45, was aware of this. Perhaps not. But one thing is clear: a conversation about her late husband stirred within her such strong emotions that she could not hold back cursing all who contributed to the heartbreak.

On Thursday, April 28 2016, Babatunde, a senior member of staff at TASCE, did not have his breakfast before leaving for the workplace, hoping to eat upon his return. He also left with only N300, after attempting to persuade his wife to hold on to all of the N500 they both had. Being a subsistence farmer, he had tilled some land for planting by the time it was evening. But the planting never took place.

He was involved in a road accident alongside colleagues, all in one of the college’s minibuses; but he suffered the greatest injury and had to be rushed to the state general hospital. It was thought that he only suffered an injury to arm but, as not all necessary tests were immediately conducted by the college, they discovered more than a year later that he in fact had his liver damaged too. A request for salary advance made to the provost for the purpose of treatment had been denied.

When her husband passed on, Bukola was giving six months of leave from work. With that free time, she took steps to get her benefits from the school and the Ogun State government, frequenting the bursary, the Ministry of Justice, the State High Court and so on. But till today, her husband’s owed salaries, pension and gratuities have still not been paid.

Babatunde had borrowed the sum of N300,000 in the past from the school’s cooperative society. Though the refund was deducted from his salaries over the years, it was not remitted to the society’s account. Now, the state government says she has to clear the debt before progress can be made, and the society is equally asking her to pay the debt before she can be given clearance. But she does not have up to that; and even if she miraculously gets the money, she asks rhetorically, how sure is she that she will get what is due to her soon after paying?

Before his demise, Babatunde always kept hope alive about his condition and the difficulty experienced at work. His wife owned a shop close to the Nigerian Television Authority’s premises and would have leased it out for extra cash but for his persistence. They will soon pay, he repeatedly said. “I don’t want you to give it to someone else such that you won’t be able to easily get it back once our entitlements are paid.”

Bukola and her late husband had been married since 1996 and she says she can never find someone like him again. His kind and generous nature did not only endear her enough to tie the knot with him, it also caused her to convert to Christianity. Her religious beliefs, the lessons he taught her, and her constant reading of the Bible are what keep her going.

Nevertheless, whenever she thinks deeply about it, she cannot help but speak strongly against those who contributed to her family’s tragic fate. “If it is true that God exists,” she says with a high-pitched, teary voice, “all the people who played a role in the death of my husband will have their reputation tarnished.

“They hurt me greatly, and may God do the same for them. On the issue of my husband’s money, I have told them it is oronro [bile]. Nobody can misuse it, and I will get it while I am still breathing. I will make use of it. They have to pay because my husband worked for it. It is his sweat.”

The unkept promise and the nagging deal

In her circle of friends and coworkers, Bukola is more commonly known as ‘Mama Ibeji’ (mother of twins). This is because she has given birth to two sets of identical twins, in addition to Sarah, a first-born daughter. While the first set of twins are enrolled in a secondary school, the second is still in primary school.

Their mum laments that paying the school fees, alongside other regular expenses such as house rent, has been gruelling, as she has to occasionally pay visits to the school administrators to plead that her kids not be sent home for defaulting.

Sarah graduated from a secondary school in Ijebu-Ode in 2017 but, for lack of financial resources, has yet to proceed to a higher institution. She has rather been attending tutorial lessons so as not to sit idly at home.

When she viewed her NECO (National Examination Council) result in September that year, she excitedly shared the good news over the phone with her dad, admitted at the time at Lagos University Teaching Hospital.

“Daddy! I cleared my NECO,” Bukola recalls her saying, and her husband had assured her he would continue working on her admission to Ahmadu Bello University once he returns from the hospital. But that promise could not be kept, as death whisked him not long after.

Before he died, Sarah had made a deal with her dad she would study to become a medical doctor. Two years later, she has refused to change her dream, despite obvious financial challenges. “I told her to consider Nursing or Microbiology, but she disagreed,” says her mum.

“I sometimes think she is naive. Where exactly does she want us to get the money? Let us just get the degree and carry on with our lives.”

*Her real name, as well as her late husband’s, is not disclosed in order not to put her job security at risk.