In Nigeria, those, who subcontract the management of the workforce prohibit trade unionism but the communities do not mobilise. The power system feeds armed groups that threaten the stability of the area.

In Nigeria, those, who subcontract the management of the workforce prohibit trade unionism but the communities do not mobilise. The power system feeds armed groups that threaten the stability of the area.

Rivers State is the main hub of the Nigerian oil industry. Since the 1990s, it has been one of the main places of confrontation between local armed groups and multinational oil companies: years of kidnappings, armed clashes, criminal militias disguised as political groups. To date, the US State Department website advises against traveling to this area of Nigeria because of "crime, riots, kidnappings and maritime crimes."

Behind this instability are the so-called "militiamen", criminal groups that control the territory and part of the local economy.

Their victims are on the one hand the oil companies, on the other the local populations, kept under threat by these organisations and forced to live in a highly polluted environment. As in every poor corner of the planet, organised crime groups have an easy game of buying the support of the local population.

According to a report by the government agency, Nigerian Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative of November 2019, between 2009 and 2018 the thefts of crude and refined oil cost the Nigerian state coffers $41.9bn. The problem is called "endemic". According to the latest statistics, it is continuously growing and with the oil crisis due to the blockade imposed by Coronavirus, it is likely that it will increase further.

There are no real investigations to find the perpetrators. The tangle of responsibilities among militiamen, minorities of communities who do business with criminals and local companies that deal with security are difficult to untangle.

There is also no political interest in finding the culprits. At the government level, the scapegoat is always the local populations.

To try to contain this problem, since 2009, the government has granted an amnesty to former militiamen in exchange for their disarmament. In 2013, the American Peace Institute, Congress Study Center, reported that "program critics believe that it has failed to eradicate the root causes of the conflict, that it is corrupt and unstable, and promotes the creation of warlords and spreads the organized crime, in addition to the rest. These criticisms are not without foundation, but often lack context and balance.

Seven years later, lights and shadows remain the same: on the one hand, the amnesty program is the only tool to involve local populations in a profound social transformation, on the other hand however, it has so far not been able to really dismantle the militia networks, which continue to exist and which in 2019 killed at least 1,031 people.

The program predicts that around 30,000 former guerrillas in exchange for renouncing weapons, can receive a salary of $420 a month and find a job. This does not always happen and many militiamen recycle themselves in the "security" sector. The government finds itself periodically threatened by ex-militia leaders to abandon the program and return to guerrilla warfare.

Some of the main actors of the Nigerian cartel led the process of the amnesty – which is a substantial part of today's problem – initially.

The first phase, in 2009, was managed by the then President, Umaru Yar’Adua, political sponsor of both Goodluck Jonathan and Abubakar Atiku.

Jonathan is originally from Bayelsa, a state bordering on Rivers. It is here that he began his political career as governor in 2005. The rise was completed with the five-year term as President that began in 2010 after Yar’Adua's death. Jonathan allegedly had contact with the top management of Eni and Shell for the negotiations of the alleged $ 1.1bn bribe on which Milan prosecutors investigate in the OPL 245 trial.

Eni through its subsidiary, Nigerian Agip Oil Company, for Nigerians Agip, has been present in Nigeria since 1962. For many people of the local communities, and many former guerrillas, working for the multinational is one of the few hopes of employment.

They use more local subcontractors, who take care of finding unskilled and low cost daily labour. The system denounced by the members of the local communities however, is unbalanced from its starting rules and legitimises a management that does not respect workers' rights, a sort of institutional corporal.

Colleagues Kelechuku Ogu and Damilola Banjo of the partner newspaper of this project, SaharaReporters, together with the researchers of the Stakeholder Democracy Network, went on site to check what is happening in a community, Egbema, among the most affected by explorations by Nigerian Agip Oil Company.

Many asked to remain anonymous for fear of consequences in the workplace. The information collected in the field dates back to January 2020.

Two flaming torches mark the entry into the territory of the Ogba/Ndoni/Egbema tribes. They burn from the oil wells extracted in these lands. Their red and orange flames are the tangible sign of a community impacted by the oil industry.

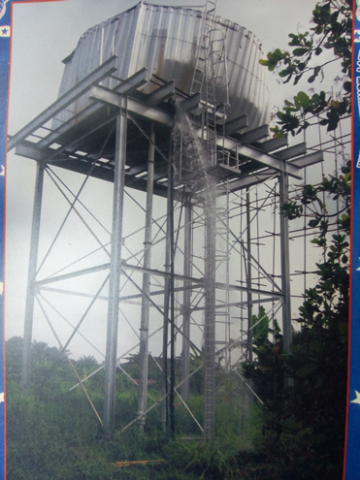

The clouds are about to unload their load of rain: after the last flood, at least a third of the Onelga territory remained without running water. Rainwater, on the other hand, invades everything: it mixes with mud and a slurry of crude oil. A protective barrier used to contain oil spills was planted to curb the muddy river. It is ineffective: oil and water have slipped into the neighbouring territories of Aggah, Mgbede and Okwuzi, three communities belonging to the Egbema.

Spills occur frequently in this land: according to data updated in September 2019 by the government's Oil Loss Monitoring Agency, over 81,000 km2 of land has been contaminated with hydrocarbons. The owner of the oil licenses is above all the Nigerian Agip Oil Company, the Nigerian subsidiary of Eni, which in these lands makes drilling in search of crude oil in 1962.

An agreement not respected

A memorandum of understanding signed between the company and local tribes is under the auspices of the government of Rivers State.

The first MoU achieved in the ONELGA region was signed in 1999 and must be renewed every four years. When we visited the region, the sixth edition of the agreement should have been in operation, but the community was still negotiating the third, in a process that had already lasted for over a year.

Copies of the agreement are in the hands of only a few people, who participate in the negotiation.

We met some young people from the Egbema community at the city gate – under a mighty mango. Despite its rarity, we obtained a copy of the 1999 memorandum. The agreement provides employment, education and infrastructure for members of communities impacted by oil drilling. All compensations that have never been seen.

“At least 90 per cent of the work done by the young people of our community – the Egbema – is occasional and does not require specialization,” explains a young man who says his name is Dagogo. To get a job, you have to turn to what the locals call "the Agip family": a group of important families, with political knowledge and connections, who manage the entire supply chain of the daily workforce. They are the ones who speak to Agip on behalf of the rest of the population. Yet, on paper, the rights of workers in the oil supply chain in the territory of ONELGA should be different.

The paragraph dedicated to the employment of the local population makes it clear that seven candidates must be employed by NAOC and four more each year enter a technical training school in the nearby city of Warri.

"The problem is that Agip doesn't want to take responsibility," adds a man who has worked with NAOC's subcontractors for 10 years. "When they hire someone, their pay belongs to them (the subcontractors). Agip knows about these illegal practices. These people have no contracts, their employer can leave them at home every day.” He was part of the negotiating team of the second memorandum of understanding. He claims that members of the "Agip family" have opposed negotiations with the company about jobs.

The Agip family

"My salary is 47,000 naira, I have nine children,” he explains, asking to keep his identity anonymous. I have been working here for 10 years.”

He is one of many employees in the supply chain through the corporals of the "Agip family". He owns land where Agip's lodgings are built for oil wells. Many in the community have some piece of land requisitioned by the company. Once a technician identifies a lot as a potential drilling site, nothing prevents the land from being obtained. Section 36 of the first program of the Petroleum Act provides that a company that holds a contract for oil exploration or for the rental of land can do whatever it wants in the affected area regardless of the owners.

In theory, the law also provides for "fair and adequate compensation for land occupation". The price, however, is not considered adequate by the premises: the most substantial compensation is N1.5m per month (3,572 euros) for 60 members of the entire family tree. Each is N25,000: 59.5 euros.

Furthermore, the remuneration is exhausted once the structure is completed. Agip repeats the payment when any form of maintenance must be performed on the well. Anyone, who considers the consideration too low and wants a job, must turn to the "Agip family".

The case of Manila Industrial Security Service Ltds

Alexander Orakwe's Manila Industrial Security Services Ltd is among the companies of the "Agip family". According to the contracts viewed by SaharaReporters, on 1 January, 2014 it was awarded the NAOC subcontracting tender for the guard of the structures.

An unfinished dispute however, raises doubts about how the company treats workers.

In 2017, Rivers State and the Federal Ministry of Labour wrote in a letter that the company deducted about N5,000 (11.77 euros) from the salaries of the people employed in 2014 and did not, as required by law, pay contributions to the Pension Fund Administrator. Journalists also have a second document in which the company renounces a meeting with state bodies to resolve the dispute. Since then, no one has tried to close the matter.

Since the litigation began, several employees have been laid off. However, they do not have whom to assert their rights: in the letter of appointment for unskilled workers in Manila, this clause was already provided: "I accept this letter of employment and I renounce joining any union or organisation".

The last advantage is for international oil companies, which can make contract labour work according to Nigerian legislation.

Not only. According to articles 2.1.3 and 2.1.4 of the draft agreement between Manila and Agip, workers are expected to be entitled to both insurance and retirement. However, none of the workers have ever had either, they say.

Local authorities

Nelson Ekperi is the prime minister of the Okwuzi community, as well as one of the "barons" of the "Agip family". His position, called "traditional government" by Nigerian laws, gives him effective power, albeit less than that of region, state and federation government. He represents the community on official occasions, including negotiations with companies.

In NAOC, he explains to journalists, in a vote from 0 to 10 gives 7. The only problem is the management of the employment policies of the communities affected by the projects: "Those who work as managers – he explains – tend to hire only their own people, without considering the host community for better occupations, such as staff directly recruited."

He adds that the hiring clause provided for in the 1999 memorandum of understanding "has not been respected to date".

"In the last MoU, there is no occupation. Industrial policy is to cause divisions within the community, creating problems within it,” he said.

Once upon a time

At one time, the working relationships between the community and NAOC were better. Ignatius Ekezie, traditional ruler of the community of Aggah, Egbema tribe, explains that once upon a time workers could aspire, after a few years to become normal employees not for subcontractors but directly with the multinational.

Today, this condition occurs much more rarely: "In Egbema today they work with Agip," he says. He then says that the first community strike was organized by the Aggah.

“We achieved a lot in that way. Now it's different. Even our young people prefer to bargain for their personal interest rather than anything else,” he said.

Contrary to the Prime Minister of Okwuzi's opinion that Agip has done enough in terms of community development, Chief Ekezie thinks otherwise. In his view, "The oil multinational has not done enough." He blames the population however, not the company because he thinks that the Egbema clan has not dealt sufficiently with the company to obtain what was rightfully theirs.

Many others seem satisfied with the current conditions in which some privileged people win tenders and works and distribute them to others who await the crumbs.

Nelson Ekperi is also among the first. The Egbema issue is a particular case: in other similar contexts in the neighbouring state of Bayelsa, disputes and challenges in court have been much more frequent.

Added to this is the ineffectiveness of the laws: the Local Content Act, written in 2010 to increase the participation of Nigerians in the oil industry, has always remained a dead letter.

In an emailed response to our findings, a spokesperson for Agip, said 60 per cent of all positions – including managerial in its firm, are occupied by persons from its areas of operation. Not satisfied with the generic nature of the reply, we tried unsuccessfully to get details on the number of persons appointed as direct staff from ONELGA. The company claimed to use industrial best practice in its negotiation with labour-level contractors.

As for servicing, where most of the staff from ONELGA reside, the firm said that is negotiated between the contractors and their employees. Agip said they do not interfere with that relationship, contradicting Mr Ekperi’s claim that the firm has an influence on what the service contract staff earn.

The Eni subsidiary went on to say that the contractors were subjected to “all laws, rules, regulations, ordinances, judgments, orders and other official acts of Nigerian and any other governmental authority recognised by the company which are now or may, in the future, become applicable to the contractor.”

The story was done in partnership with the Italian reporting Project Italy, and developed with the support of the Money Trail Project (www.money-trail.org)