This block of power holds firmly in hand most of the affairs of the emerging African country. The names of the members are also associated with the main cases of corruption, misappropriation of public funds and alleged bribes that have passed through Nigeria in recent years. These also include the alleged $ 1.1bn stick for the OPL 245 oil license disputed between Eni and Shell.

In Nigeria there is a power group that crosses African borders through, which the country's most important economic interests pass. His every decision affects 220 million inhabitants.

An international political, economic and financial cartel that branches from Nigeria to the United States via Lebanon, Dubai, the Netherlands and Italy. His interests lead to the development of a new business district in Lagos: Eko Atlantic City.

Within the project, foreign entrepreneurs, who have made their fortune, former army generals, local politicians and businessmen converge. A red thread that goes from the entrepreneurs of Lebanese origin Gilbert and Ronald Chagoury to the former dictator, Sani Abacha, to the businessman and leader of the political party PDP (in opposition today), Abubakar Atiku, and his right hand, the entrepreneur Italian Gabriele Volpi.

This block of power holds firmly in hand most of the affairs of the emerging African country. The names of the members are also associated with the main cases of corruption, misappropriation of public funds and alleged bribes that have passed through Nigeria in recent years. These also include the alleged $ 1.1bn stick for the OPL 245 oil license disputed between Eni and Shell.

The OPL-245 trial

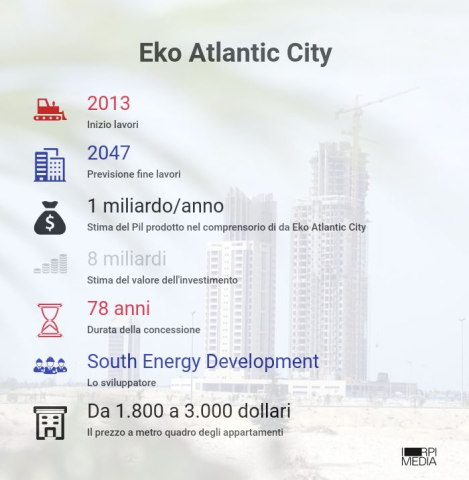

The development of Eko Atlantic City began in 2013 and was entrusted without tender to a subsidiary of the Chagoury group, a family business that has grown to 20,000 employees today led by brothers Gilbert and Ronald Chagoury. The project was proposed by their South Energyx Development, based in the United Arab Emirates. Born in Lagos in the second half of the 1940s to Lebanese parents, the Chagoury brothers are the promoters of Eko Atlantic. If this real estate development exists, it is thanks to their network of contacts between Nigerian and international politicians they managed to obtain a 78-year concession.

According to a report by the Nigeria Export Processing Zones Authority, the investment will be worth a total of $8bn, largely covered by four Nigerian credit institutions and by two international banks ready to guarantee the possible shortcomings of the former. Another entrepreneur works on the area together with the Chagoury, the Nigerian-Italian. Gabriele Volpi, known in Italy above all because he is the patron of the historic water polo company, Pro Recco and Spezia Spezia, which currently plays in Serie B. Volpi's investment, through three companies, Intels, Orlean Invest and Prime Property, to date it is $150m for phase one of development.

The Chagoury and Foxes are closely linked to pieces of Nigerian power, the former to the Abacha family, the latter to Abubakar Atiku. Both ended up under the magnifying glass of the American authorities for helping to bring public funds out of Nigeria that their political godparents had misappropriated. Reconstructions always denied by those directly concerned.

However, the United States Senate Standing Committee, which for a year investigated the issue of corruption in Nigerian political leadership, put down on white as "for a period of eight years from 2000 to 2008" Atiku and his wife had been in able to "bring over $40m of suspicious funds to the United States mainly through transfers sent by offshore companies", many of these attributable to Volpi himself. Gilbert Chagoury, on the other hand, defined by African business analyst, Philippe Vasset, as "the guardian of the Abacha presidency", following the death of Sani Abacha in 2009, agreed to return about $300m stolen from Nigeria by the dictator through his network of companies.

Eko Atlantic, the floating city at the crossroads of money and politics

Operations starting immediately. A forest of skyscrapers. Fountains, paths, vertical woods. In fact, Eko Atlantic will be a free zone, capable of producing one billion a year of GDP for Nigeria, the twenty-sixth world economy and first in Africa if we look only at gross domestic product. A fully independent city and home to the big oil companies and the wealthy of the city, with apartments ranging from $1,800 to $3,000 per square meter and exclusive hotels. Surrounded by a protective wall of rocks, this peninsula of 10 square kilometres of sand dredged by the sea is the bet to drive out the recession that since 2014, after years of growth, affects the economic life of the country. Many believe in this project worthy of the ambitions of the Emir of Dubai, first of all the administration of Lagos, which has given the Emirate society of the Lebanese brothers Chagoury a 78-year concession on the fields at stake.

The project has been approved, or at least "publicised", also on an environmental level, as a barrier to stop the erosion of the Lagos coast. The environmental impact study attached to the project states that "it is a more complete and permanent solution to address the persistent erosion problem, which is likely to be exacerbated by climate change and the increase in storms", which often causes deaths and floods in these areas. Hence, says the study, the need for the Lagos protective wall project and Eko Atlantic City. However, there are other evaluations that come to opposite conclusions, and see in the skeletons of skyscrapers under construction the omen of a future Atlantis. Remember Quartz Africa in a 2017 article that the environmental impact could produce the opposite effect for Lagos: starting from the poor neighbourhoods that are at water level, without anything protecting them from the tides, that the wall of Eko Atlantic City will head straight for them.

At the moment, the recovery of the plain is well under way, but not yet complete. From the boats with which the inhabitants of the slums shuttle between the two shores of the Lagos lagoon, the city emerged from the water appears far from being operational. Satellite images confirm this: for the most part, Eko Atlantic City is an expanse of sand, 90 million cubic meters to be exact. Visiting it is impossible: "We appreciate the interest, but we don't give interviews at this time", the press office cuts short. The works completed to date are the Pearl towers (where someone already lives), the skeletons of the three towers of the Azuri Peninsula to the South and the three buildings of Eko Energy City to the North, the Alpha 1 Tower and part of the road system.

The delays can be found not only in the crisis in the Nigerian economy but also in the fear that is in investing in Nigeria after the renewed attention of local authorities on money laundering through real estate projects. The latter trend is enhanced by the anti-corruption campaign of President Muhammadu Buhari, which unleashes the investigative bodies very easily, only to arrive at modest results.

The doubts surrounding this project are not few. It seems impossible to transform an area lying at the mouth of a gray-green lagoon into a paradise for wealthy investors and tourists, constantly plowed by oil tankers and in the centre of a dense network of oil pipelines pumping crude oil towards the land. As much as the city is changing at full speed, the dream of becoming a new Dubai is still far from being realised. And those who risk being excluded, such as the evicted from the community on the opposite side of the Lagos lagoon, in Tarkwa Bay, are the clear majority of the 22 million inhabitants of Lagos.

The irresistible rise of Eko Atlantic developers

Both the Lebanese brothers, Chagoury, and the Italian, Volpi, began their ascent in the years when General Babangida, together with his deputy, General Sani Abacha, led Nigeria. The latter in 1993 became president with a coup d'état and history has dismissed his five-year presidency as a bloody dictatorship. Under him, the writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, soul of the Ogoni people, was sentenced to death, who first denounced the environmental destruction committed by the oil multinationals, Shell at the top, in the Niger Delta region.

The Chagoury are not only close to the Abacha family, but they are also financiers and members of the Clinton Foundation, which in turn immediately believed in the Eko Atlantic City project. "Everyone knows I'm a friend of the Clintons," Gilbert Chagoury told Frontline reporters in 2010. The foundation in 2009 pledged to secure the Eko Atlantic City project, promoting access to credit for a billion dollars. The Clintons' closeness cost some criticism at home, especially after the conservative Fox News broadcaster dusted off the news of an agreement in full conflict of interest – which the US State Department, led by Hillary at the time, had signed for the purchase of land in Eko Atlantic City.

Over time, the brothers capitalised on the US interest in the project so much that in May 2019, despite the change of administration at the White house, Chagoury Group signed an agreement between Eko Atlantic, represented by Ronald Chagoury in person, and the American Government for a new consulate right on the peninsula. After all, the two Lebanese brothers are able to move with politics: from the mid-nineties until 2017 Gilbert was diplomatic representative for the island of Santa Lucia, one of the main tax havens in the world: first as a UNESCO delegate, then as an ambassador at the Holy See. Another trait in common with Gabriele Volpi, who also enjoys good friends in the Vatican.

But it is once again the Abacha family that act as a link between the kings of money of Eko Atlantic, Ronald and Gilbert Chagoury and Gabriele Volpi. Mohammed Sani Abacha, son of the former dictator, founded in 1998 and controls - via nominee - with former Petroleum Minister, Dan Etete, Malabu Oil and Gas, the company that holds the Opl245 oil license. This license, according to investigations by the Milan prosecutor for which the trial is currently underway, would then have been transferred to Eni and Shell, after the payment of a bribe of $1.1bn to Nigerian public officials.

During the hearings for the Opl 245 trial, Volpi was nominated only a few times, and is not among the suspects. Instead, he is a key person in the second investigation into Eni conducted by the Milan Public Prosecutor's Office, that of the false plot against the CEO, Claudio Descalzi. According to the accusatory hypothesis, the former legal consultant of Eni Piero Amara, together with collaborators and magistrates compliant in Trani and Syracuse, would have devised this intricate strategy to block the Opl 245 trial with a new judicial investigation. Eni has always rejected the hypotheses, claiming that Amara acted on its own. But according to the testimony of former oil technician, Massimo Gaboardi, one of the alleged entrepreneurs, who from Nigeria would try to bring down Descalzi, would be Gabriele Volpi in collaboration with businessmen active in Italy, Nigeria and United States. Curious circumstance: they are united by their closeness to the Clinton Foundation, with which everyone collaborates.

The Milan prosecutor's office is trying to unravel this inextricable tangle of truth, lies and simple coincidences. From Nigeria, there is at least one certainty: Eko Atlantic City, the Clinton friends' project, is the real estate deal of the century in Lagos.

This story was done in partnership with the Investigative Reporting Project Italy and developed with the support of the Money Trail Project (www.money-trail.org)