In the last couple of years, overcrowding in Nigeria custodial centres has become a great burden on the justice system. In this investigation, JULIANA FRANCIS examines the staggering amount of taxpayers’ money spent on awaiting trial inmates, arising from poor administration of the justice system

Kevin Odu, 32, has been in prison since February last year. He was arrested by proxy, arraigned and remanded for a crime allegedly committed by his kinsman who lived with him.

“He stole my neighbour’s laptop and generator and disappeared. I was arrested because police couldn’t find him,” Odu said.

He said the police arrested him and arraigned him for a crime he did not commit, after failing to arrest the alleged culprit.

He was granted bail, he said, but could not meet the bail conditions.

Since then, Odu has been kept in prison, awaiting trial for offences he allegedly did not commit, joining thousands of Nigerians who languish in such conditions for either minor crimes or accusations they are innocent of.

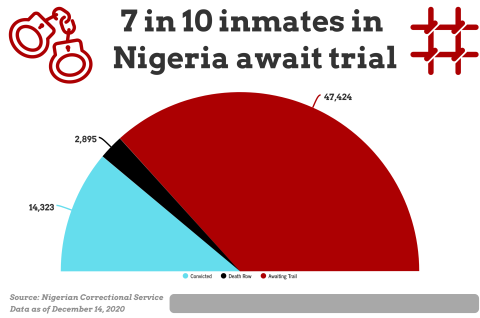

In Nigeria, more than two-thirds of the prison population are awaiting trial inmates, or ATM in prison parlance, most of whom are facing minor offences and many of them have been granted bail conditions they could not fulfil.

By last December, the number of awaiting trial inmates in 275 custodial centres nationwide was about 47,424, a figure prison officials said could have been more if not that the coronavirus pandemic forced the Nigeria Correctional Service (NCS) to start screening for the virus before admitting new inmates.

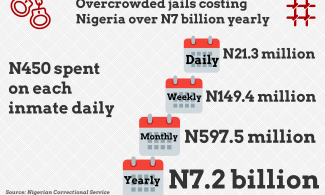

The Federal Government spends about N450 daily on each inmate, amounting to N21.3 million daily and about N7.6 billion annually on awaiting trial inmates alone.

But lawyers told the New Telegraph that there should be no reason to keep someone like Odu in prison for this long, arguing that alternative punishments should be adopted to reduce prison congestion and channel taxpayers’ money to better investments.

The National Chairman of Prisons and Hospital Ministry at the Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG), Pastor Ariyo Popoola, who has been involved in prison ministry and reform for years, said a shocking number of awaiting trial inmates have no business being in prison.

Popoola said as more inmates are being released through interventions of pro-bono lawyers, human rights activists and religious bodies, more are being remanded.

Both those with minor and felonious cases spend years waiting for judgement that never comes as many of them have not had any court appearances for a long time.

“There are inmates on remand who have been abandoned and forgotten by policemen,” said a prison official who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorised to speak to the press.

“These policemen are their investigating police officers (IPOs). We discovered this problem after the #EndSARS protest. Many police stations were burnt and in the process case files were destroyed. There are ATMs, who have been forgotten by their IPOs because their case files cannot be found or have been burnt.”

Lawyers and human rights activists say that the problems of awaiting trial are compounded by the failure of various stakeholders, mainly the police and judiciary, to adhere to the Administration of Criminal Justice Act (ACJA) and Administration of Criminal Justice Law (ACJL).

Under the Act and law, the courts are supposed to facilitate speedy trials and alternative sentencing, whereby accused persons with minor offences are sentenced to community service.

Good laws, poor implementation

Barrister Samuel Akpologun, a Lagos-based lawyer, said the ACJL replaced the Criminal Procedure Law, introducing revolutionary provisions and measures aimed at promoting transparency, credibility, accountability and efficiency of the criminal justice administration in Nigeria.

Akpologun said ACJL and ACJA aim at achieving speedy trial of criminal cases, commencement of trial at magistrates’ courts within 30 days and completion of trial matters within 180 days. According to him, the law provides for non‐custodial alternative sentencing.

A human rights lawyer, Justus Ijeoma, who is also the Executive Director of the International Human Rights and Equity Defence Foundation (I-REF), explained that non-custodial alternative sentencing means punishment other than imprisonment.

“There are a lot of forms of alternative non-custodial sentencing, which include verbal sanctions, conditional discharges, and status penalties like denying him or her positions of trust for certain years, restitution, where an offender is mandated to restore what he had taken from a victim of the crime. There’s also suspended or deferred sentencing, there are fines as means of punishment, among others,” he said.

Ugonna Ezekwem, expert on Justice Sector Reforms, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), said non‐custodial alternative sentencing includes suspended sentences, community service, curfews, and parole orders, among others.

Chain reaction of flawed system

For the court to give speedy trial, police must have to rise to the occasion by conducting a thorough investigation and arraigning the suspects on time. In most cases, the police have failed in this duty.

Raphael Ashy, 31, had spent 12 months at Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), Ikeja, Lagos Command, before being taken to court. Ashy, who is presently in Kirikiri Maximum Prisons awaiting trial, has already spent six years in prison for a crime he insisted that he did not commit.

“These days, I pray every day to God to bring someone to rescue me out of this hell,” Ashy told the New Telegraph. “I can’t even begin to imagine what my aged mother has been going through all these years.”

Ashy said he was framed up by some boys residing at the Railway Station area of Ebute-Metta in Lagos. He said it was a mere street fight which was then suddenly labelled as a robbery case and he was subsequently arrested by the police.

Popoola, the RCCG pastor, who also identified as a former convict, said that only a flawed judicial system could keep someone like Ashy in prison for that long without any conviction.

“The law says that suspects should be taken to court within 24 hours, but police can keep suspects in cell for three months, sometimes six months,” Popoola said. “I’ve seen someone detained in a police cell for two years. After detaining some of these suspects for weeks, the police station will then transfer them to the command, claiming they have jurisdiction and again, they would be detained at the command's cell.”

The problem is compounded when cases get to the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) and courts after police’s poor and shoddy handling, thereby leading to prison congestion.

“The police are major witnesses in cases, but when the case is called, these policemen will not be around. Sometimes, you’ll hear the IPO, who is in charge of the case, has been transferred to another state. And these policemen are the ones that are supposed to bring evidence to court. When they are not available, the cases are adjourned and the inmates continue to be on remand,” Popoola said.

While the failure of the police is obvious, Popoola pointed out that there are not enough judges and magistrates to adjudicate cases.

But the judges are also responsible for the problems of awaiting trials as they set outrageous bail conditions for minor offences, according to lawyers.

“Yes, the judiciary has got a chunk of the blame,” said Ijeoma, the human rights lawyer. “There is a need to promote human rights as envisaged by the administration of criminal justice.”

Still the judges are not the last in the chain of blame for the disproportionate number of awaiting trial inmates.

“Inmates contribute money to fuel vehicles in order to be taken to courts, but ordinarily, the government is supposed to fuel these vehicles,” Popoola said. “If the accused is not taken to court and his case is called, it will be adjourned and he continues to be ATM.”

Distance between prison and court as excuse

The Kirikiri maximum, medium and female prisons have inmates whose trials are ongoing in about 28 different courts around Lagos.

But the vehicles to take these inmates to these different locations are few. The warders are then forced to look at the greater number of inmates heading to courts in a particular location and take those, leaving others for another day.

Chiamaka’s case has stalled since 2015, in the female Kirikiri custodial centre where she has been an inmate over a case of child abuse. The court, where her case is being heard and her detention centre are far flung. This is being cited as the reason why she did not have any court appearances for three years.

“I had a lawyer, but I was never lucky to appear in court. I’m in Kirikiri Prison, while the court is at Epe,” Chiamaka said. “Every time, before my lawyer gets to Epe, the court would have been over. It has been quite frustrating. Epe is almost on the outskirts of Lagos State.”

A human rights lawyer, Pamela Okoroigwe, of Legal Defence and Assistance Project (LEDAP), who has now taken over Chiamaka’s case, said: “The punishment for Chiamaka’s offence is between three to six years, but Chiamaka has spent over six years in prison and that matter has not come up for trial. She has completed the sentence without trial. We’re tired and now thinking of going for plea bargaining, but the trial has not started and the judge refused to grant bail.”

Mallam AbdulFatai Oshun, who spent nearly seven years at Ikoyi Prison, also blamed the distance between the court and the prison for his long imprisonment. He said he was accused of killing his younger brother but later discharged and acquitted last September through the intervention of LEDAP.

During his imprisonment, Oshun said he had 49 adjournments, with one lasting for a year and two months.

“Inmates are supposed to be taken to courts Mondays to Fridays, but at Ikoyi Prison, inmates are taken to Epe court only on Friday because of lack of vehicles,” he said.

His experience led him to uncover a troubling situation, he said. “I realised something while in prison; a large number of people on ATMs are innocent people, with some not knowing their offences. Many were raided by the police.”

That was the ordeal of Henry John who was dismissed from the Army after his return from remand this year. John said he was serving at Maiduguri and decided to visit his soldier-friend in Abuja. Then, one day he went to a bar for a drink and got into a fight with four men.

He was arrested and detained at the police station as one of the injured men’s brothers insisted that John must pay N50,000 for medical bills.

“Unfortunately, my phone and ATM card got missing during the fight,” John said. “I couldn’t call anyone and didn’t have money to pay for anything. Nobody knew where I was. When I was arraigned, the magistrate asked me to pay N30,000 to the complainant or go to prison.”

He was on remand until last February when Prisoners Rehabilitation and Welfare Action (PRAWA) showed interest in his case.

After his release, John said he was arrested by the military police for deserting and detained for two weeks before being dismissed.

Justice delayed, still justice denied

Last December, the President of the Court of Appeal, Justice Monica Dongban-Mensem, condemned heavy dockets comprising over 4,630 Appeals and 6,207 Motions pending in the Lagos Division.

Dongban-Mensem stated that there were a total of 345 appeals, comprising 289 Commercial Appeals; 10 Human Rights Appeals; and 46 Criminal Appeals which were scheduled for hearing.

According to her, the 345 scheduled Appeals for hearing represent only eight per cent of the total number of Appeals in Lagos Division.

The Executive Secretary of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), Tony Ojukwu Esq, noted that most of the awaiting trial inmates in correctional centres are arrested for minor offences like begging, hawking, loitering, failure to pay debts, among others.

According to him, many inmates have been on awaiting trial for longer than necessary, which is in blatant violation of their human rights as guaranteed by the African Charter of Human and People’s Rights.

A human rights lawyer, Gabriel Aigbonosimuan Giwa-Amu, who is also the founder of Steven and Solomon Foundation, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) against injustice, blamed the problems of awaiting trial inmates on harsh government policies and laws as well as other factors like incompetent judiciary.

“There should be professional bailors to act as surety for persons granted bail,” Giwa-Amu suggested. “When an inmate is in custody for a period exceeding one month, he or she should be released on bail to responsible surety with or without an application for bail. Secondly, criminal cases that carry a maximum sentence of less than three years, the defendant should be allowed to go on bail on personal recognisance except his flight risk is proven to the court.”

The Lagos State Public Relations Officer, NCS, Barrister Rotimi Oladokun, explained that the reasons for many inmates being on awaiting trial are multi-dimensional, which include many stakeholders being involved in the administration of the criminal justice system.

He said: “We have been advocating that those key players in the administration of the criminal justice system should be proactive. This is because once the ingredients of crimes are there and they have proven it, I’m sure there will be quick dispensation of justice.”

Reacting to allegations that NCS Lagos State didn’t have enough vehicles to take inmates to courts, Oladokun said: “The command has been fortunate because the Controller-General has made interventions in providing more vehicles. Even though we have inadequacies, it’s better than it used to be. There’s a great improvement. We take inmates to court as and when due, based on their adjournment dates.”

He also denied the allegations that inmates fuel vehicles in order to be taken to courts. “The reforms started by the Controller-General of the NCS, Ja’afaru Ahmed, made sure that funds and resources are provided for the running of our custodial centres.

“If we really want to ensure that the number of ATMs reduces, then we have to know that it’s not all offences that should be criminalised. It’s not all offences that should go through a full adjudication process.”

The Executive Director of Rule of Law and Accountability Advocacy Centre (RULAAC), Okechukwu Nwanguma, said the police have contributed immensely to the problems of awaiting trials.

“Research has found that the majority of persons in prisons are persons awaiting trial over minor or in many cases false allegations brought against them by the police because such persons refused or could not provide money for bail while in police custody. So, maliciously, the police will charge them to court and they are either ordered to be remanded in prison or are granted bail, unable to fulfil their bail conditions and end up spending weeks and months or even years in prison awaiting trial thereby compounding the crisis of prison congestion.”

Nwanguma suggested that persons charged and convicted of minor offences should not go to prison, adding that the Attorney-General and Minister of Justice and State Attorneys-General, should initiate steps for audit of police cells and correctional centres, including juvenile correctional facilities, to decongest them.

Justice Olushola Williams (rtd) said the issues boil down to enforcement and implementation, adding that there are many factors that contribute to delays in adjudication.

“Imagine a situation where a police officer, who investigated a case and is already testifying in court, gets transferred to a new station or state entirely,” Justice Williams said. “Getting that officer to come back to court becomes a huge challenge because most times, his colleagues cannot even give a precise detail of his whereabouts or newly assigned post. That police officer's absence automatically stalls the trial. What I'm saying is that judges and lawyers cannot always be the cause of delayed trials.”

•This report is funded by the Civic Media Lab, under its Criminal Justice Reporting Fellowship, with support from MacArthur Foundation