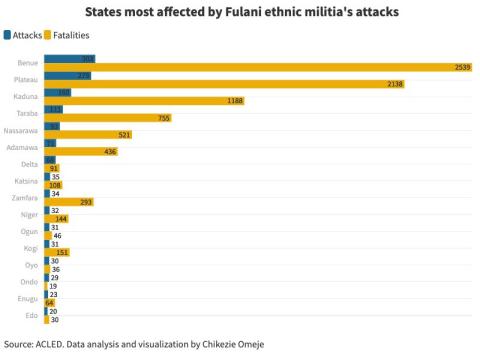

Backed by a militia, they have raided communities for no less than 1481 times, killing nearly nine thousand people in Nigeria.

Fulani herdsmen arouse terror.

Backed by a militia, they have raided communities for no less than 1481 times, killing nearly nine thousand people in Nigeria, according to Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).

When they attack communities, they kill anyone they could, including children and women. They burn down houses in their usual overnight raid, displacing those who survive their invasion.

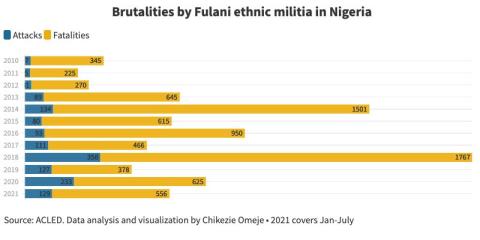

But as the Fulani herdsmen have intensified their terrorism over grazing rights with more than 120 attacks and 500 deaths in the first half of this year, several communities have managed to sustain peace with the pastoralists.

"We have taken our time to understand that the first step towards maintaining peace with herders is to avoid tampering with their cows,” said 75-year-old Festus Bagi, a retired civil servant from Akabe whose community has never been attacked by Fulani herdsmen.

Akabe demonstrates that farmers and Fulani herdsmen can live together without bloodshed. But maintaining peace in this community in Bassa-nge district in Bassa Local Government Area of Kogi State comes with both farmers and herders making sacrifices to accommodate one another.

Here in Akabe, on the edge of the River Niger and reachable by boat from Lokoja, Christian farmers and Muslim pastoralists share more than the same air. They fetch water from the same stream, trade in one market and exchange gifts.

“Yes, we do have a misunderstanding with them mostly on how to control their cows from straying into our farms but we do engage them for dialogue instead of violence,” Bagi said. “Our community should be celebrated as one of the most peaceful communities in this state,” he added.

The lingering conflict between farmers and herders has often been fueled by a dispute that spirals into violence and reprisal killings. It often starts when cows feed on crops and the farmers retaliate by killing the cows. Then the herdsmen fight back by killing the farmers and their children as well as burning down their houses. In Benue and Plateau, the most affected states, hundreds of thousands of farmers have been displaced because of this cycle of violence.

Choose dialogue over violence

In Akabe, misunderstanding between farmers and herders arises but it has never led to violence. They engage in dialogue.

In March when 32-year-old Victor Awom, a youth leader, received a complaint about a farm destroyed by cows, he chose to discuss compensation with the herders.

“We went to see the leaders of the herders in their settlement and a delegate was sent to come and verify the claims and later some compensations were paid,” Awom said.

He remembered an incident that could have escalated into violence, but they again chose dialogue. "It was when the herders allowed their cattle to defecate and contaminate our village stream which also serves as our only source of water,” Awom said. “We approached them as well. Finally, it was resolved, and we now secured the stream with security wires and padlocks."

In Akabe, farmers do not fight the herders or kill their cows when they intrude into their farms. The farmers inform their community leaders who then engage with the leaders of the herders.

That has been the experience of Victoria David, a 57-year-old farmer whose crops have once been eaten up by cows.

"The herders meddled in my farm and destroyed my crops, but I had to involve the leaders from the community who approached the herders and they paid me some compensation," David said.

She had encountered herders around her farm many times, and she cautioned them to mind her crops which they had obeyed. But the intrusion often happens at night when it is hard to know the perpetrators.

“Many farmers who have lost their crops here find it difficult to get compensated because it mostly happens at nights when everyone is asleep,” David said. “I believe most of the herders tampering with the farms at night are not the ones staying here in the village. You know they usually move from one location to another during the night."

Learn how to let go

Forgiveness also plays a role in how Akabe has been able to keep peace with the pastoralists, like when cows fed on the crops of 20-year-old Safiyat Kabiru. The herders pleaded, she said. She forgave them, she said, and did not even report the incident to her community leaders.

“The younger ones are carefree,” said Kabiru, who tied her baby to her back with a basket on her head. “They sometimes allow their cattle to stray into our farms. And when you catch them, you see them pleading and asking for mercy.”

Thomas Edih, 67, a Christian preacher had to forgive the herders when cows damaged his farm last year. “I met the herders myself and after much negotiation, they agreed to pay a certain amount as compensation,” he said. “Well, I accepted just for peace to reign, because the agreed amount wasn't commensurate with the actual cost of the damaged crops.”

Despite the transgression, Edih said he has been relating with herders without bitterness. “During harvest, I give them from my groundnuts and yams,” he said, adding that the herders had never been rude to him.

The cordial relationship with the pastoralists in Akabe has lasted over generations, according to Awom Elisha, the village head of Akabe. "The Fulani herders have lived here with us right from the days of our grandparents,” he said.

But Elisha is now worried that the current herders have become more emboldened and reckless, destroying their farms, and contaminating their source of water. “The sentiment shared by all of us remains that, if the movement of these herders can be controlled, the fight and tension would reduce and the government should do something about this," Elisha said.

Seek mutual accommodation

Rice, yam, groundnut, and cassava farms were in view on the path to the Fulani settlement in Akabe. Over a hundred huts dotted the place with Fulani children playing around.

Their leader, 55-year-old Saidu Abdullahi, described the Akabe as good people, pointing out that he has lived here for about a decade.

“Whenever our cattle or goats damage their crops, we go to them and plead with the farm owner,” Abdullahi said. “We pay for the damages. We are very happy, and our families are here with us. We brought them because we have peace here.”

He added: “There is no problem. The community even gave us plots of land to cultivate. Sometimes, we go to their houses to get drinking water and other things.”

Abdullahi advised pastoralists in other places to “always find a way to engage leaders of their host communities to find solutions when there is disagreement instead of fighting."

A Fulani woman, Binta Adamu, said she had been living in Akabe for the past nine years. “They treat us nicely,” she said. “No one has threatened me. We go about our businesses without harassment."

While Akabe has been able to nurture peace with the pastoralists, such arrangement is not sustainable, according to Mark Adebayo, the executive director of SecureWorld and Liberty Initiative for Peace, a non-profit organization that advocates for peace.

"The fastest panacea to the menace is to immediately ban open grazing and indiscriminate movement of cattle among sedentary populations," Adebayo said. “People cannot continue to die for cattle to survive. That's unacceptable.”